With the WHO reporting newly confirmed Nipah virus cases in West Bengal, India and Asian countries rushing to tighten airport health screenings, the world is once again on alert for a deadly pathogen. Nipah virus periodically re‑emerges in South and Southeast Asia, and even a handful of cases draw global attention because of the virus’s exceptionally high fatality rate, which can exceed 50% in many outbreaks. The virus combines three high-risk features: zoonotic spillover from wildlife reservoirs, documented human-to-human transmission, and the absence of approved vaccines or targeted antivirals. These characteristics place Nipah virus among a small group of pathogens with clear epidemic and pandemic potential. Its inclusion in the WHO’s R&D Blueprint for priority pathogens reflects the severity of disease and persistent gaps in medical countermeasures.

Virology of Nipah virus: Molecular architecture and host invasion

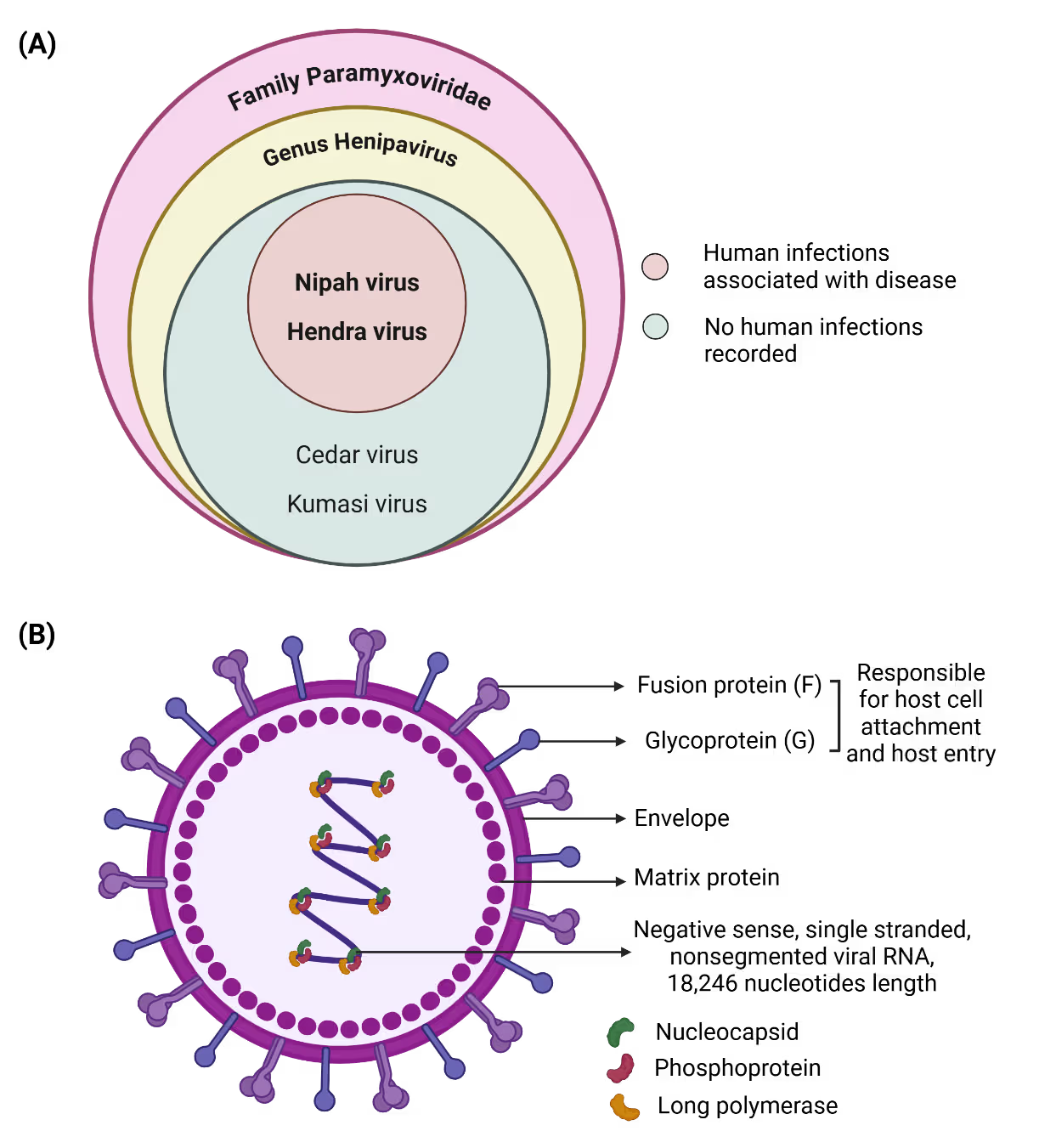

Nipah virus is an enveloped, negative-sense, single-stranded RNA virus with a genome of approximately 18.2 kilobases that belongs to the paramyxoviridae family (Figure 1A). The genome encodes six major structural proteins that coordinate viral replication, assembly, and host cell entry. Among these, the attachment (G) and fusion (F) glycoproteins are central to host tropism and pathogenicity (Figure 1B).

Nipah virus uses the ephrin‑B2 and ephrin‑B3 receptors, which are widely conserved and expressed in endothelial cells, neurons, and respiratory epithelium, enabling infection across multiple organs and species. After entry, the virus suppresses interferon signaling, allowing rapid replication and causing widespread endothelial injury, vasculitis, and central nervous system inflammation. Evidence of relapsing and late‑onset encephalitis suggests that Nipah can persist in immune‑privileged sites, though the mechanisms of this long‑term persistence remain poorly understood.

Spillover geography and transmission pathways

Nipah virus outbreaks have been reported in Malaysia, Singapore, Bangladesh, India, and the Philippines, showing a concentrated yet varied spillover landscape. The first major outbreak occurred in Malaysia (1998–1999), where pigs acted as amplifying hosts and facilitated large-scale animal-to-human transmission, with additional spread to Singapore through imported pigs. Since 2001, Bangladesh has experienced near annual outbreaks primarily linked to consumption of bat-contaminated raw date palm sap and subsequent human-to-human transmission, a pattern also observed in India, especially in West Bengal and Kerala. In the Philippines, outbreaks have involved horse-to-human transmission followed by person-to-person spread. Across affected regions, case fatality rates remain high (40–75%) and often rise during outbreaks dominated by interpersonal transmission. This person‑to‑person spread typically occurs through direct contact with bodily fluids of infected individuals, including saliva, respiratory secretions, blood, and urine, with additional risk from contaminated surfaces and close‑range exposure to respiratory droplets in crowded or poorly ventilated settings. Environmental change and increasing bat-human interface continue to elevate spillover risks, underscoring the need for coordinated One Health surveillance (Figure 2).

Natural reservoirs

Fruit bats of the family Pteropodidae, particularly Pteropus species, are the confirmed natural hosts of Nipah virus. These bats do not develop overt disease but they shed the virus through saliva, urine, and excreta. Viral shedding intensifies in pregnant bats during winter, coinciding with the date palm sap harvesting season in endemic regions. Pteropus bats are widely distributed across South Asia and northern Australia.

Infection in domestic animals

Multiple domestic animals, including pigs, horses, goats, sheep, cats, and dogs, have been infected during past outbreaks, with pigs playing a central role during the 1999 Malaysian epidemic. Infected pigs can shed virus even during the 4-14 day incubation period. Farm-to-farm transmission can occur via contaminated items such as equipment, clothing, boots, or vehicles.

Clinical spectrum of disease: From febrile illness to fatal encephalitis

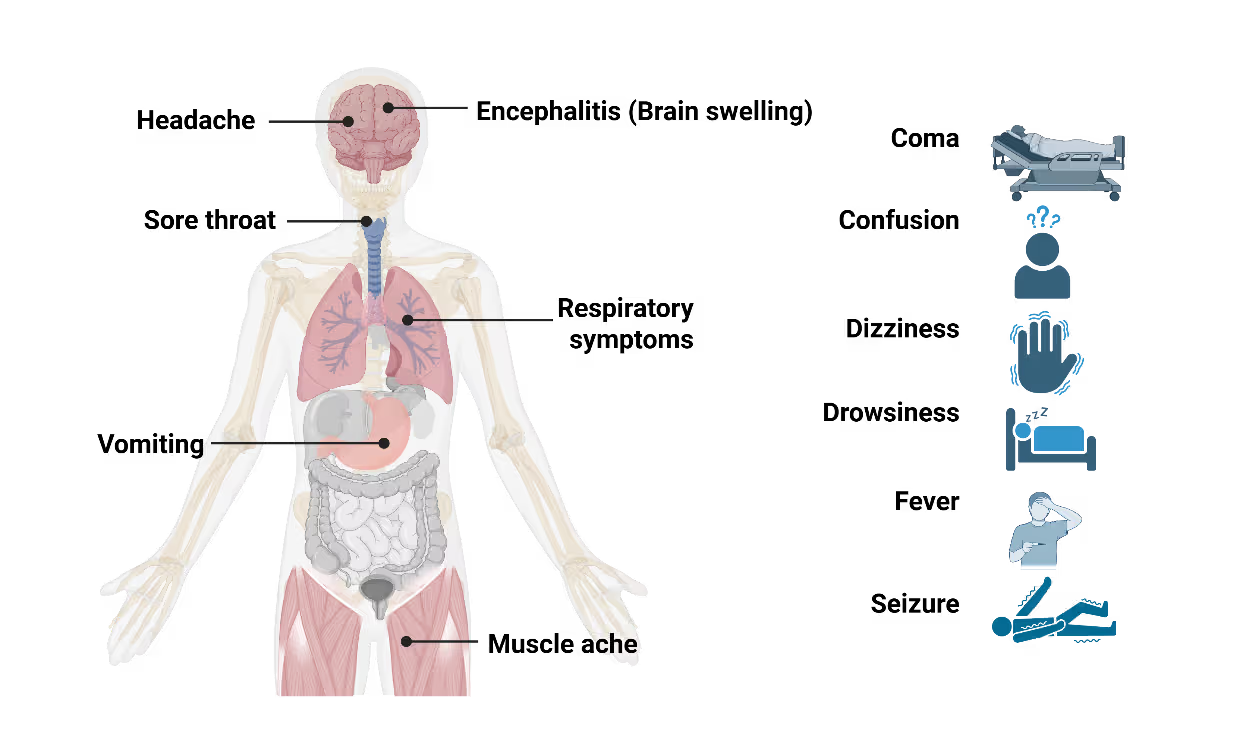

Nipah virus infection presents with a wide clinical spectrum, ranging from mild or asymptomatic cases to rapidly progressive, fatal disease. Initial symptoms are non-specific and include fever, headache, myalgia, and vomiting, making early clinical diagnosis challenging, particularly in resource-limited settings. Neurological involvement is the hallmark of severe disease. Patients may develop acute encephalitis characterized by altered mental status, seizures, and coma within days of symptom onset (Figure 3). Respiratory involvement, including cough and acute respiratory distress, is more frequently observed in outbreaks with sustained human-to-human transmission and is associated with higher mortality. An unusual and clinically significant aspect of Nipah virus infection is the occurrence of delayed or relapsing encephalitis. These cases, reported months or even years after apparent recovery, underscore the need for long-term follow-up of survivors and complicate assessments of disease burden. The incubation period typically ranges from 4 to 14 days but can extend beyond 40 days in rare cases. This prolonged incubation window poses challenges for contact tracing and outbreak containment, particularly during large exposure events.

Research landscape and publication trends

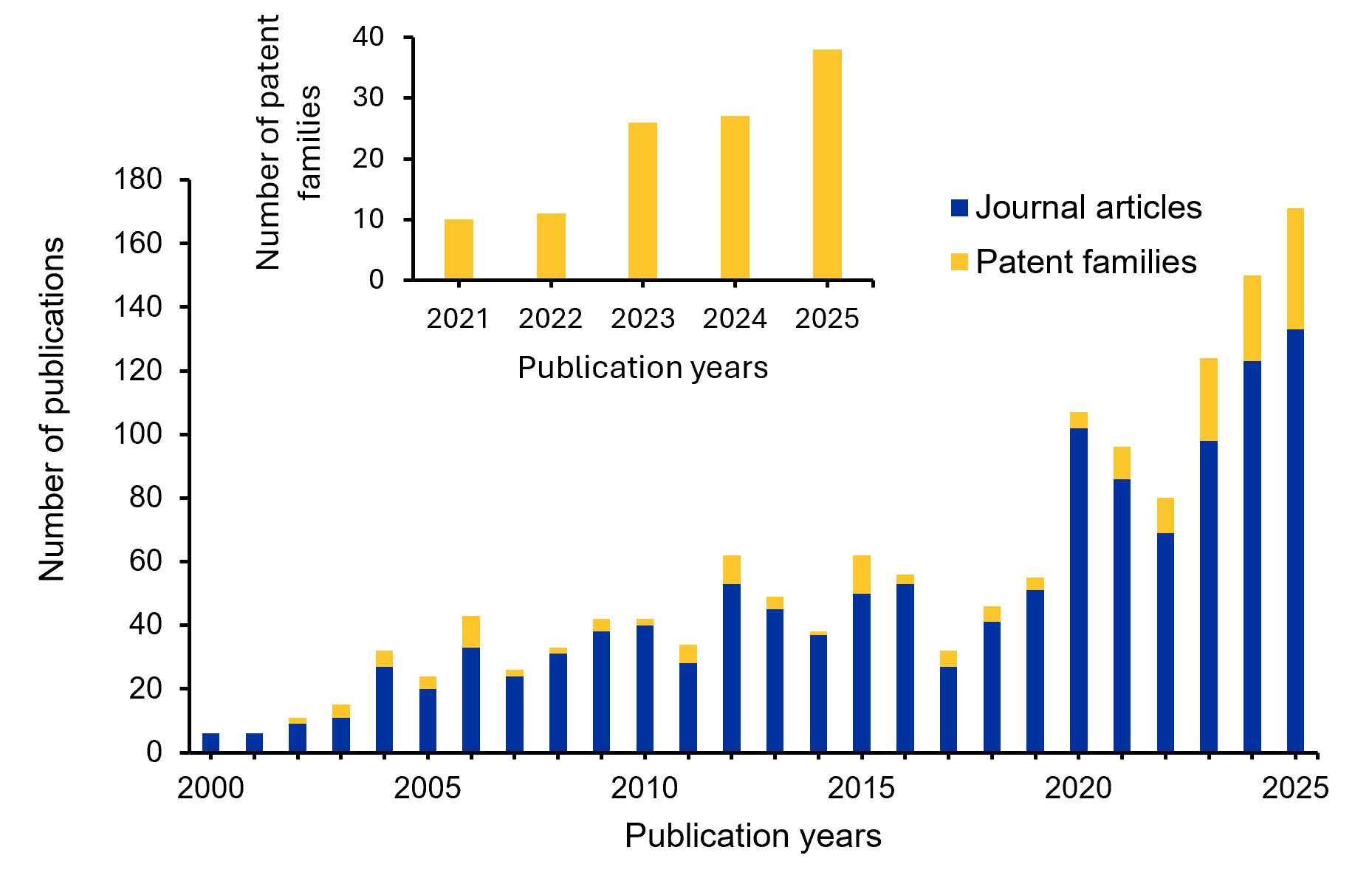

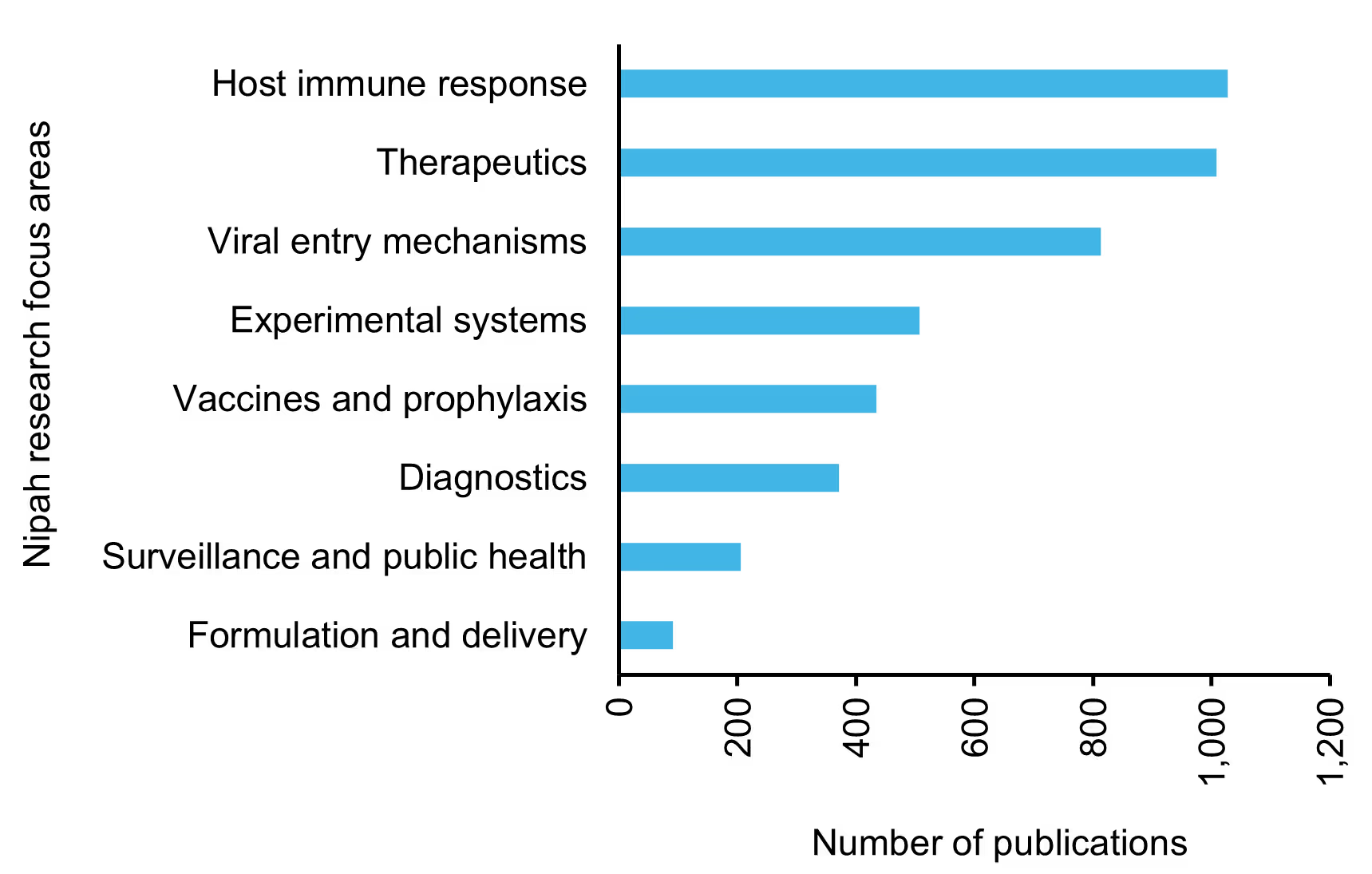

We leveraged the CAS Content Collection™, accessed through CAS IP Finder™ powered by STN™, to analyze global journal publication and patent activity related to Nipah virus. Year-wise trends reveal a steady increase in research output over the past 25 years (Figure 4), with a pronounced rise after 2018 driven by intensified outbreak events and broader recognition of high-risk zoonotic threats. Journal articles remain the dominant form of scholarly output, while patent filings, particularly in the areas of diagnostics, therapeutics, and vaccines, have expanded significantly since 2020. The inset analysis of the last five years shows that patent activity increased from 10 families in 2021 to 38 in 2025, representing an overall 280% growth (~3.8 fold) and a compound annual growth rate of ~39.6%. By 2025, scientific publications and patent activity reach their highest levels, reflecting sustained R&D investment and a strengthened global research focus.

Research is most concentrated in understanding host immune responses, therapeutic development, and viral entry mechanisms, underscoring a strong interest in pathogenesis and intervention strategies. Moderate publication volume is observed in areas such as experimental systems, vaccines, prophylaxis, and diagnostics, whereas surveillance, public health, and formulation and delivery remain relatively underexplored. Together, these insights reveal a research ecosystem driven primarily by mechanistic and therapeutic investigations, with notable gaps in translational readiness and outbreak preparedness.

Using CAS SciFinder® to access the advanced patent‑discovery capabilities of the CAS Content Collection™, we identified a set of recent, high‑relevance patents in Nipah virus R&D. These are summarized in Table 1.

Diagnosing a high-consequence pathogen: Tools and limitations

Accurate and timely diagnosis of Nipah virus infection is critical for outbreak control but remains logistically challenging. Due to the non-specific nature of early symptoms, laboratory confirmation is essential. Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assays are the primary diagnostic tool for detecting viral RNA in acute cases. Serological assays, including enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) for IgM and IgG antibodies, play an important role in retrospective diagnosis and sero-surveillance. Virus isolation and neutralization assays provide definitive confirmation but require biosafety level 4 (BSL-4) containment, severely limiting their accessibility.

In outbreak settings, delays in diagnosis can have significant consequences, allowing continued transmission before infection control measures are implemented. The need for rapid, point-of-care diagnostic tools that can be deployed in decentralized healthcare settings remains a critical unmet need in Nipah virus preparedness.

Therapeutic interventions: Limited options and experimental approaches

Currently, no specific antiviral treatment has been approved for Nipah virus infection, and patient management relies primarily on supportive care. However, ongoing research into antiviral agents, monoclonal antibodies, and host‑targeted therapies continues to expand the landscape of potential interventions.

Recent computational drug‑repurposing studies have highlighted five FDA‑approved antivirals, Saquinavir, Nelfinavir, Simeprevir, Paritaprevir, and Tipranavir, as promising candidates. These compounds demonstrated strong binding affinity to the Nipah virus glycoprotein, host receptor complex, and exhibited stable interactions in molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations, suggesting their potential for further in vivo and clinical evaluation.

Beyond repurposed antivirals, several experimental molecules, nucleoside analogues, interferon inducers, and monoclonal antibodies have shown varying degrees of efficacy in in vitro, in vivo, or animal model studies. The following table (Table 2) summarizes key drugs and biological therapeutics under investigation for their potential activity against the Nipah virus. Among these, m102.4 is currently in Phase I clinical trials.

Vaccine development landscape: Progress amid structural challenges

Nipah virus vaccine development has accelerated in recent years, driven by its designation as a priority pathogen and increased investment from global health preparedness efforts. Multiple platforms, including recombinant subunit vaccines, viral‑vector-based candidates, and nucleic‑acid technologies, are being evaluated across preclinical and early‑phase clinical studies. An overview of the major candidates and their development status is summarized in Table 3-4.

Despite encouraging progress in the laboratory and early clinical evaluations, advancing these candidates toward licensure remains challenging. The sporadic and geographically limited nature of Nipah outbreaks makes traditional efficacy trials difficult to conduct, underscoring the need for alternative regulatory pathways, adaptive trial designs, and region‑specific preparedness strategies.

Conclusion and future outlook

Nipah virus continues to be an emerging pathogen of significant concern. Not only because of its high fatality rate but also due to the complex ecological and molecular factors that sustain its reemergence. As research accelerates across virology, therapeutics, and vaccine development, it is steadily closing knowledge gaps that have long hindered preparedness. Rapid diagnostic advancements, targeted antivirals, and innovative vaccine platforms reflect a broader and more sophisticated R&D ecosystem than at any point since Nipah’s discovery. Yet, the sporadic and geographical nature of outbreaks continues to slow the path from promising laboratory findings to actionable countermeasures. Future progress will depend on strengthening One Health surveillance, improving community‑level early detection, and expanding clinical trial infrastructure in regions where spillover risk is the highest. With sustained investment, cross‑sector collaboration, and adaptive regulatory strategies, the coming decade holds real potential for transformative discoveries. Reducing the global threat of Nipah virus will require scientific innovation but also the long‑term integration of ecological, public health, and clinical insights into cohesive outbreak‑prevention strategies.