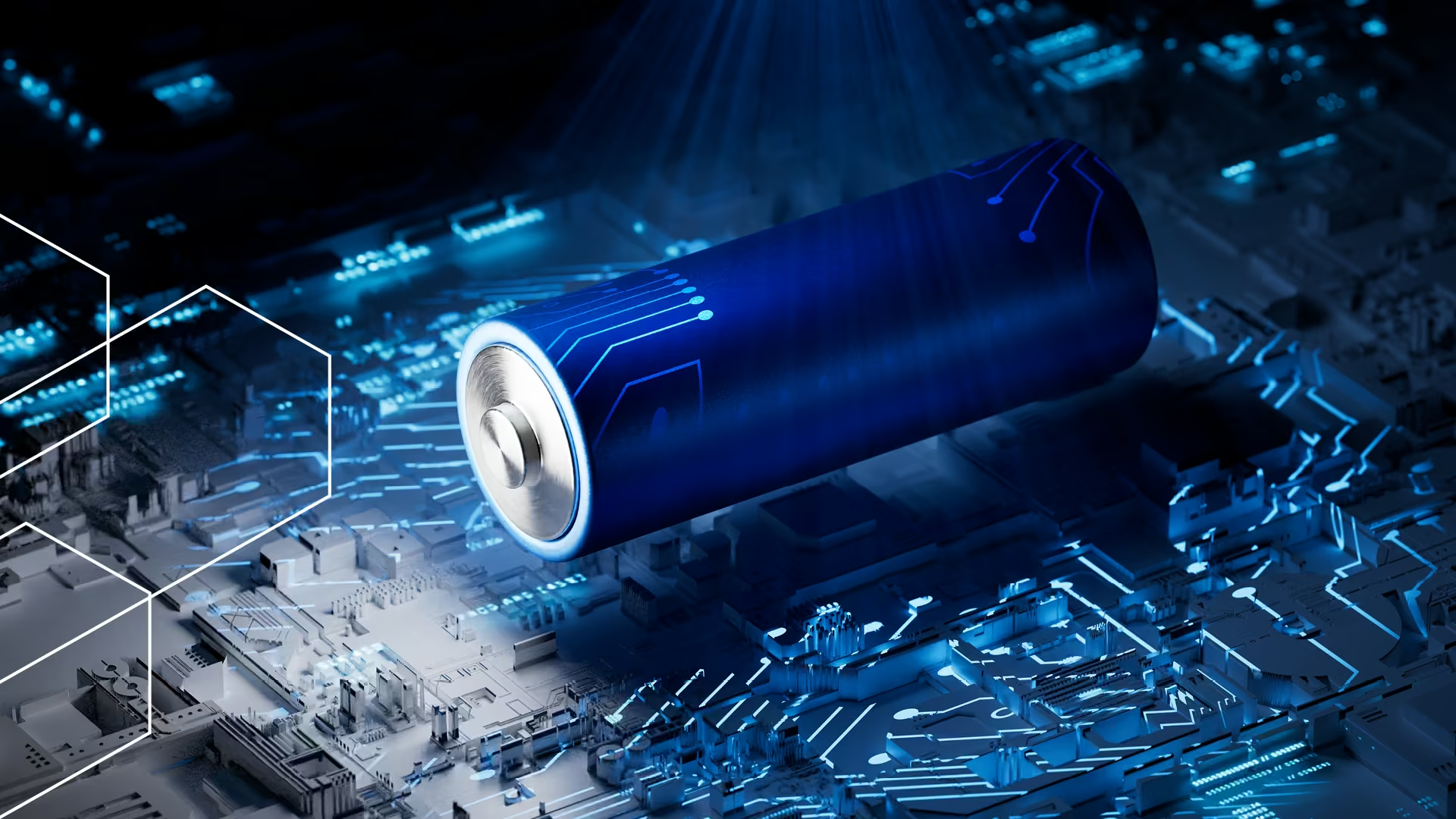

Emerging Science

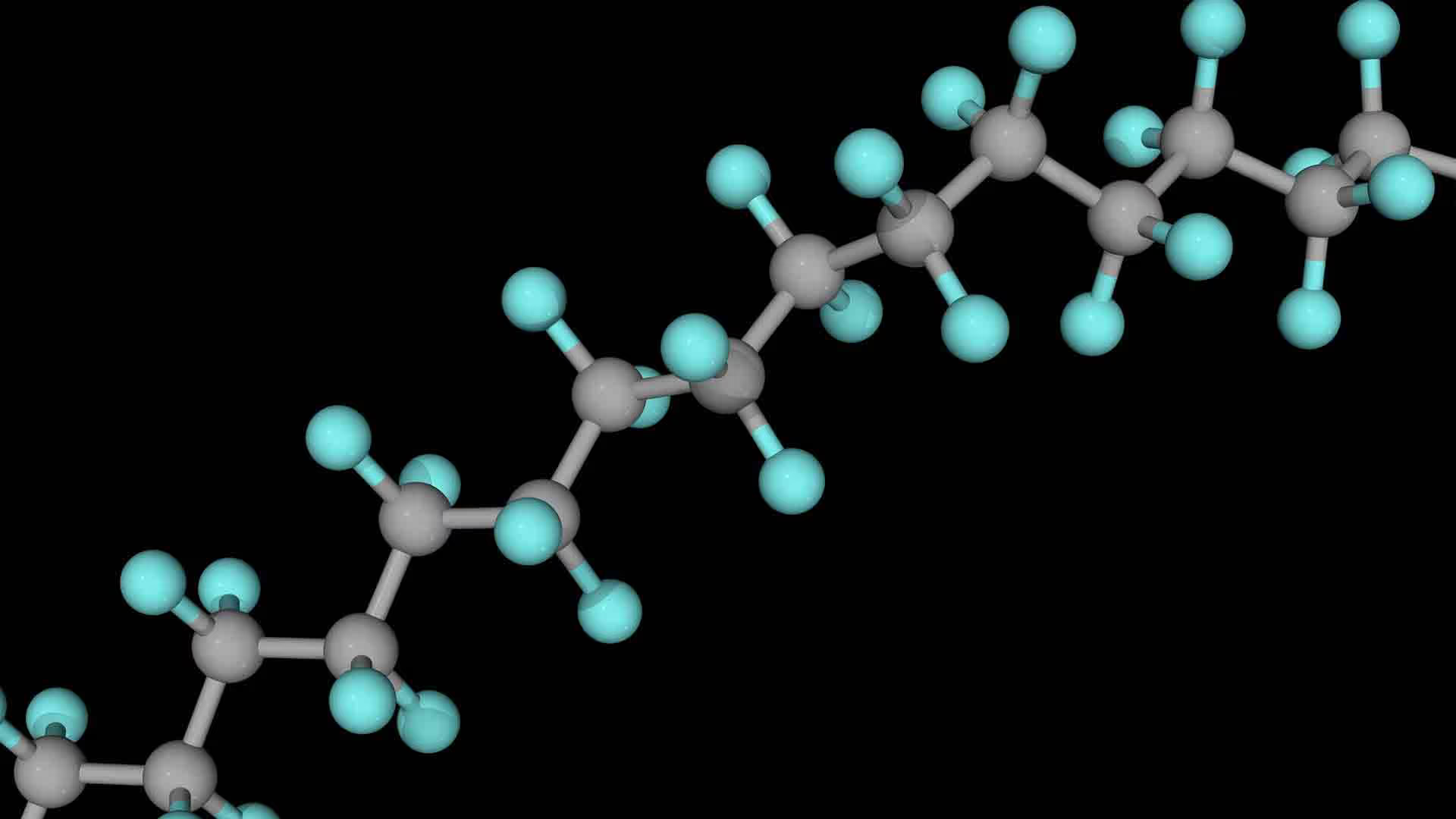

How solid-state battery technology is changing energy storage

Solid-state batteries take lithium-ion technology to a new level with greater energy density, longer lifespan, and improved safety.

Read the reportRead the articleDownload the summarySee the infographicRead the publicationRead the recapWatch the video