エピジェネティクスは、DNA配列の変更を伴わない遺伝子発現の遺伝的変化を研究する分野で、生物学や医学における革新的な分野として浮上しており、遺伝子発現が内部および外部刺激に応じてどのように調節されるかを明らかにしつつあります。エピジェネティクス制御は、発生生物学、疾患の発症、遺伝子と環境の相互作用、世代を超えた遺伝、治療法の開発の基礎となっています。エピジェネティクスは、遺伝子が静的なゲノムを超えて動的に制御される仕組みを解明することで、遺伝学と環境の影響を結び付け、疾患のメカニズムや革新的な治療戦略に関する洞察を提供します。

当社は、人間の手によって収集された最大の科学情報リポジトリであるCASコンテンツ・コレクションTMを分析し、エピジェネティクス研究の進展をたどって、新たな主要コンセプトと課題を特定しました。この包括的な分析では、現代の生命科学と医療に影響を与える科学的基盤、臨床応用、技術革新を検証しました。

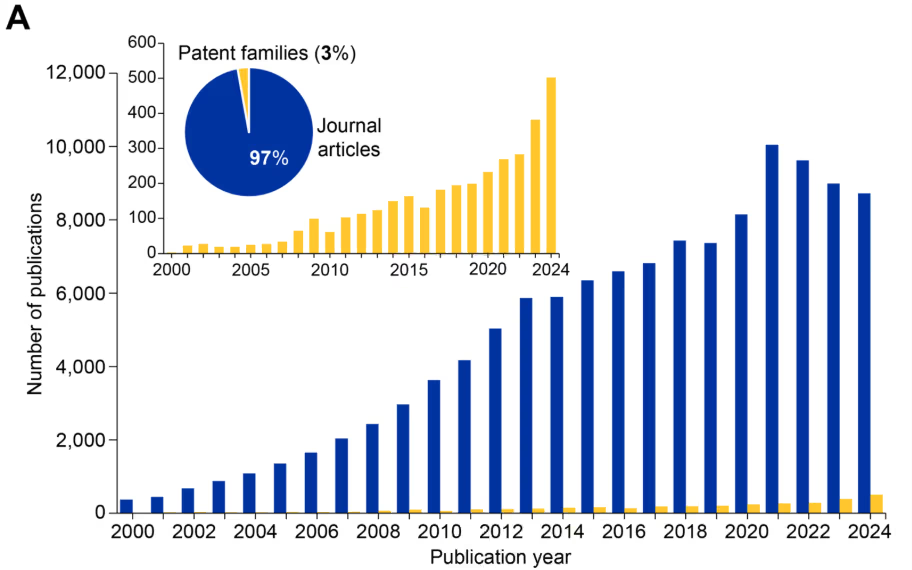

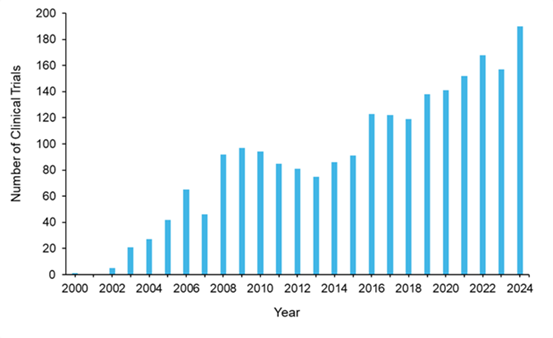

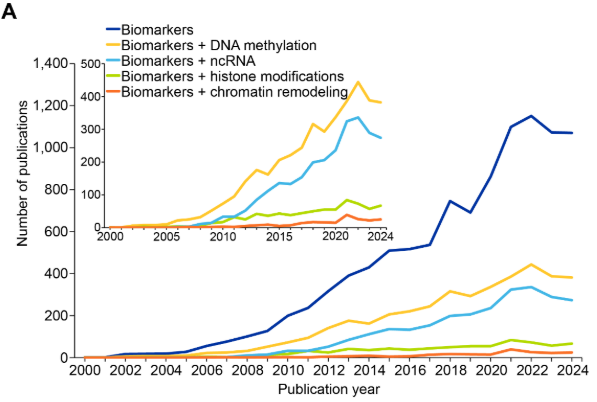

当社の分析では、過去20年間でエピジェネティクス関連の文献数が急激かつ継続的に増加しており、現在CASコンテンツ・コレクションにはこの分野の文献が12万件以上収録されていることがわかりました(図1参照)。エピジェネティクス分野内では、文献数はジャーナル記事が97%を占め、残り3%が特許となっています(図1A参照)。これは、エピジェネティクスがまだ発見と検証の段階にあることを示しています。

しかし、特許件数の急増(図1Aのグラフ参照)は、急速に進化するこの分野に対する商業的関心と翻訳可能性が高まっていることを示しています。注目すべきことに、2014年以降、エピジェネティクスの文献数は遺伝学の文献数を上回っています(図1B)。また、2020年以降に顕著なこととして、エピトランスクリプトミクスが独自の分野として台頭してきています(図1B)。

この成長軌道は、資金の大幅な増加と一致しており、研究資金の総額は2004年の2億ドルから2024年には45億ドル以上に増加し、年間約2,700件のプロジェクトが支援を受けています(図1C参照)。プロジェクト数と資金調達額が着実に増加し、平均プロジェクト資金調達額が120万ドルから170万ドルに増加していることは、政府と民間部門がエピジェネティクス研究とその臨床応用を推進することに継続的に取り組んでいることを浮き彫りにしています。

エピジェネティクスの商業的重要性は劇的に拡大しており、2023年に18.4億米ドルと評価されている世界のエピジェネティクス市場は、2033年までに67.7億米ドルに達すると予測されています。この成長は、がん治療用のアザシチジン(Vidaza®)やボリノスタット(Zolinza®)など、FDA承認の10種類以上のエピジェネティクス薬によって推進されています。また、臨床試験中のエピジェネティクス療法は35種類以上あります。これらの候補は主にさまざまな悪性腫瘍を対象としていますが、がん以外の多様な分野にも見られ始めています。

エピジェネティクスがどのように進化し、医学の将来にどのような意味を持つのかを理解するために、さらに詳しく見ていきましょう。

エピジェネティクス制御の中核メカニズム

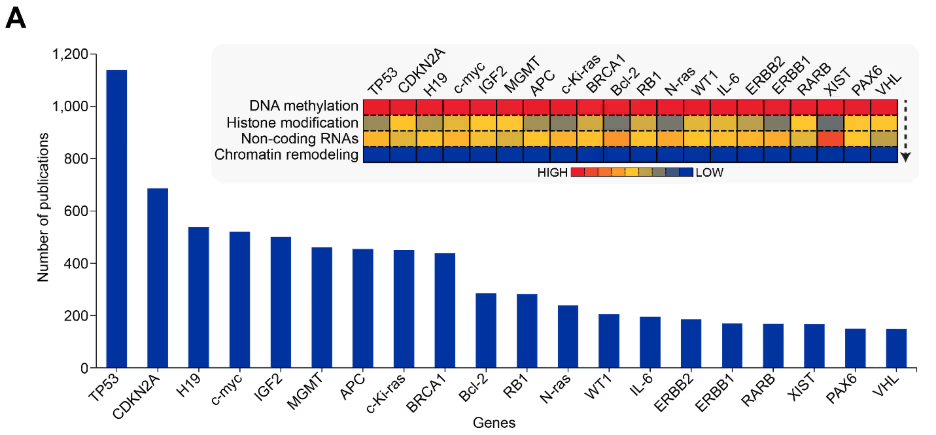

エピジェネティクスのメカニズムは、DNA配列を変更することなく、DNAとクロマチン構造の化学的修飾を通じて遺伝子発現を制御します。これらのメカニズムは、DNAメチル化、ヒストン修飾、ノンコーディングRNA(ncRNA)調節、およびクロマチン・リモデリングという4つの主要なクラスで構成されます。エピジェネティクス関連の文献を調査したところ、当初はこれらのメカニズムを扱った文献はほとんど見つかりませんでした。この分野は2000年代初頭に確立されたため、これは当然の結果といえます(図2参照)。

その後、4つのメカニズムすべてが成長を加速させ、中でもDNAメチル化は最も急激な増加を見せ、ジャーナル文献と特許文献の両方においてこの研究分野を支配するようになりました。他のすべてのメカニズムでも同様に増加が見られ、医薬品開発におけるエピジェネティクス・ターゲットの認識が高まっていることを示唆しています。

DNAメチル化

DNAメチル化は、DNA中のCpGジヌクレオチドのシトシン環にメチル基(–CH₃)を付加し、転写抑制を引き起こす基本的なエピジェネティクス・メカニズムです。この修飾はX染色体の不活性化、ゲノム・インプリント、トランスポゾン抑制において重要な役割を果たします。

DNAメチル化はDNAメチルトランスフェラーゼ(DNMT)によって触媒されます。DNMT1は複製中に既存のメチル化パターンを維持し、DNMT3a/3bは発生中に、または環境からの刺激に応じて、新しいメチル化パターンを確立します。DNMT3Lは触媒活性を欠いており、主に初期発生段階で発現し、成人期には生殖細胞と胸腺に限定されます。DNMTは、CpGジヌクレオチドの出現頻度が高い領域であるCpGアイランド(遺伝子プロモーターの近くにあることが多い)を標的とします。

がん、心血管疾患、精神疾患、アルツハイマー病、自閉症、メタボリック・シンドロームなど、さまざまな疾患で、異常なメチル化パターンが特定されています。腫瘍抑制遺伝子プロモーターの過剰メチル化は、腫瘍形成を促進する遺伝子発現を抑制しますが、全体的な低メチル化は、がん遺伝子を活性化し、ゲノム不安定性を引き起こす可能性があります。DNAのメチル化パターンは加齢とともに変化し、エラーの蓄積やメチル化維持の忠実度の喪失などが起こります。

ヒストン修飾

ヒストン修飾は細胞分裂を通じて受け継がれ、環境要因の影響を受け、発達や病状に影響を与える可能性があります。アセチル化、メチル化、リン酸化、ユビキチン化などの翻訳後ヒストン修飾は、クロマチン構造と遺伝子アクセシビリティを変化させます。ヒストン・アセチルトランスフェラーゼ(HAT)と脱アセチラーゼ(HDAC)は、ヒストンからのアセチル基の付加と除去を触媒することでアセチル化を調節します。一方、メチルトランスフェラーゼ(HMT)と脱メチラーゼ(HDM)はメチル化を制御します。これらの修飾は主に、ヌクレオソーム・コアから突出してアクセスしやすくなっているヒストン・テールのリジン、アルギニン、セリン、およびスレオニン残基で発生します。

ヒストン修飾は、遺伝子発現、DNA修復、有糸分裂中の染色体凝縮を制御するヒストン・タンパク質の周りにパッケージ化されたDNAであるクロマチンの構造に影響を与えます。異常なヒストン修飾は、遺伝子発現パターンを破壊し、腫瘍の発生や転移の一因となる可能性があり、アルツハイマー病、ハンチントン病、自閉症、加齢に伴うクロマチンの変化、免疫調節不全などの他の病気や障害にも関連しています。

これらの変化は多くの場合「ヒストン・コード」を形成し、異なる残基の修飾の組み合わせによってクロマチンの状態が微調整され、相乗効果が生じたり拮抗したりします。これらはクロマチン構造と遺伝子発現を制御する動的かつ多用途なシステムであり、その可逆的な性質により治療介入の有望な目標となっています。

ノンコーディングRNA(ncRNA)

ncRNAは、タンパク質をコードすることなく、遺伝子発現とクロマチン動態において重要な調節的役割を果たす多様な調節分子群を構成しています。これらのRNAは、メッセンジャーRNA(mRNA)の分解を標的としたり、転写機構を調節したりすることで、遺伝子発現プロセスを微調整します。

主要なエピジェネティックな調節因子として、マイクロRNA(miRNA)、長鎖非コードRNA(lncRNA)、およびpiRNA(PIWI相互作用RNA)の3つのクラスが明らかになっています。これらのncRNAは、主に次の5つのメカニズムを通じてエピジェネティックな調節機構を統合的に制御します。

- クロマチンリモデリング:lncRNAは、特定のゲノム領域にクロマチン修飾複合体を動員し、クロマチン構造と遺伝子発現を規定します。たとえば、X不活性化特異的転写産物(XIST)は、ポリコーム抑制複合体2(PRC2)を動員することでX染色体の不活性化を媒介します。

- 転写調節:miRNAとlncRNAは、転写因子もしくはRNAポリメラーゼと相互作用することによって転写を調節します。たとえば、lncRNA HOX転写物アンチセンス遺伝子間RNA(HOTAIR)は、PRC2を動員して別の染色体上の遺伝子を抑制します。

- 転写後の調節:miRNAは標的のメッセンジャーRNA(mRNA)の3′非翻訳領域(UTR)に結合し、分解もしくは翻訳阻害を引き起こします。lncRNAは分子スポンジとして機能してmiRNAを隔離することで、mRNAが標的にされるのを防ぎます。

- RNA修飾:一部のncRNAは、RNAのメチル化(例:N6-メチルアデノシン、m6A)や編集を誘導し、RNAの安定性や翻訳に影響を与えます。

- ゲノム防御:piRNAとsiRNAは転移因子を抑制し、ゲノムの完全性を保護します。siRNAは、反復配列を有する領域においてテロクロマチン形成を誘導できます。

クロマチンリモデリング

クロマチンリモデリングは、ユークロマチン(開放、転写活性状態)とヘテロクロマチン(凝縮、転写不活性状態)の間でクロマチン構造を動的に改変します。クロマチンの基本単位はヌクレオソームで、DNAがヒストンタンパク質のオクタマーに巻き付いた構造をなします。クロマチンリモデリングは、スイッチ/スクロース非発酵性(SWI/SNF)、イミテーションスイッチ(ISWI)、クロモドメインヘリカーゼDNA(CHD)結合タンパク質、およびINO80ファミリーなどのATP依存性複合体によって行われ、ATPの加水分解を利用してヌクレオソームの再配置、排出、あるいは再構築を行います。

リモデリングのメカニズムには、ヌクレオソームのスライディング、ヒストンの除去/交換、クロマチンの凝縮/解凝縮が含まれます。これらのプロセスは、DNAメチル化やヒストン修飾を用いて、遺伝子発現、細胞分化、および同一性維持を調節します。

クロマチンリモデリングの調節異常は、がん、神経障害、発達障害と関連しています。たとえば、ATリッチ相互作用ドメイン1A(ARID1A)(SWI/SNF複合体の構成要素)などのクロマチンリモデラーの変異は、悪性腫瘍で頻繁に観察されます。クロマチンリモデラーは、異常遺伝子発現を逆転させる有望な治療標的となっています。そのため、クロマチンリモデリングは、環境要因(食事、ストレス、毒素など)が遺伝子発現や健康に及ぼす影響の媒介因子として認識されています。

エピジェネティクスにおける最近の進展

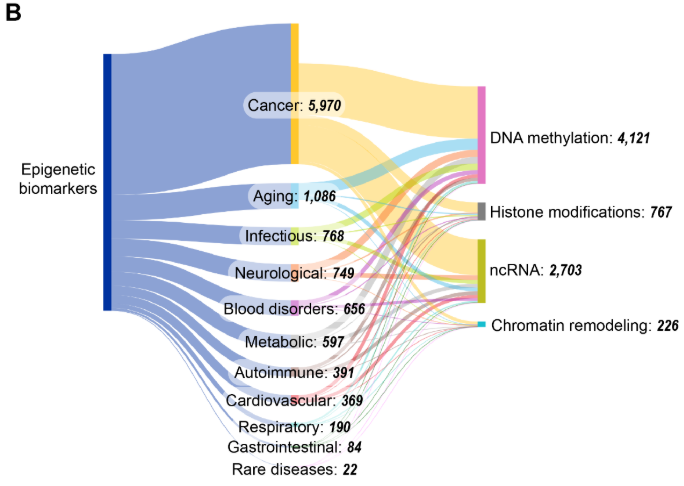

最近の進展により、DNAメチル化、ヒストン修飾、ncRNA調節、クロマチンリモデリングといったエピジェネティック修飾が、特にがんにおいて、疾患の病態形成にどのように寄与するかが明らかになってきました。miRNAやその他のncRNAがエピジェネティックな調節因子として機能するという新たな研究により、新しい治療標的が特定されている一方で、個々のエピジェネティックプロファイリングの進歩は、オーダーメイド医療アプローチの進展を促進しています。文献の動向は主要な関心分野を示しています(図3参照)。

環境エピジェネティクス

食事、ストレス、毒素、生活習慣などの環境要因は、前述したさまざまなメカニズムを通じてエピジェネティックな変化を引き起こす可能性があります。これらの変化は、細胞機能や組織の恒常性を変化させることで、がん、代謝障害、神経疾患などの発症に寄与する可能性があります。具体的な影響は以下の通りです。

- DNAメチル化パターンに影響を及ぼす栄養素(葉酸、ビタミンB12など)の利用可能性。

- 化学物質曝露(ビスフェノールA、農薬、大気汚染物質など)は、エピジェネティックなマーカーを変化させ、長期的な健康への影響をもたらします。

- 心理的および生理的なストレスが、ストレス反応遺伝子のエピジェネティックな変化を誘発し、精神的健康を調節します。

- エピジェネティック状態を調節することにより疾患リスクに影響を与える生活習慣要因(喫煙、飲酒、身体活動レベルなど)

エピトランスクリプトミクス

エピトランスクリプトミクスは、RNA分子に対する化学修飾と、遺伝子発現および細胞機能の調節において果たす役割の研究に焦点を当てています。エピジェネティクスがDNA配列そのものを変えずに遺伝子発現に影響を与えるDNAやヒストンの修飾を解明するのと同様に、エピトランスクリプトミクスはRNA修飾がRNAの安定性、翻訳、スプライシング、その他のプロセスにどのように影響するかを解明します。

mRNA、tRNA、rRNA、およびncRNAにおいて170種類以上の異なるRNA修飾が同定されており、N6-メチルアデノシン(m6a)は真核生物のmRNAにおいて最も豊富で広く研究されている修飾です。主要な修飾には以下が含まれます。mRNAの安定性、スプライシング、核外輸送、翻訳に影響を与える、アデノシンのN6位でのm6Aメチル化、mRNAおよびtRNAのシトシンN5位に生じ、RNAの安定性と翻訳に影響を与えるm5Cメチル化、ウリジンの異性体でありRNAの安定性と翻訳効率を高めるシュードウリジン(Ψ)、および塩基対形成特性を変化させスプライシングやタンパク質コードに影響を与える、アデノシンからイノシンへの脱アミノ化。

エピトランスクリプトミクス機構は、主に次の3つのタンパク質クラスから構成されます。

- 「ライター」:修飾を加える酵素(m6Aメチル化のためのMETTL3/METTL14複合体など)。

- 「イレイサー」: 修飾を除去する酵素(脂肪量および肥満関連タンパク質(FTO)およびm6A脱メチル化のためのalkBホモログ5、RNA脱メチル化酵素(ALKBH5)など)。

- 「リーダー」:RNA修飾の動態を総体的に調節する、修飾されたRNAを認識し結合するタンパク質(m6A認識のためのYTHドメインタンパク質など)。

RNA修飾は複数の細胞プロセスを調節し、これらの修飾の調節異常はさまざまな病理に寄与します。がんにおいては、m6A修飾は腫瘍で頻繁に変化し、腫瘍の進行、転移、薬剤耐性と関連しています。RNAの異常な編集と修飾は、アルツハイマー病、パーキンソン病、筋萎縮性側索硬化症(ALS)などの神経変性疾患と関連しています。さらに、HIVやSARS-CoV-2などのRNAウイルスは、宿主のRNA修飾機構を利用して、エピジェネティック修飾を含むウイルス複製と免疫回避を調節します。

ハイスループットシーケンシング技術により、RNA修飾のゲノムワイドマッピングが可能となり、修飾の検出と定量化には質量分析法と化学的標識技術が補完的に用いられています。これらの進歩は、RNA修飾酵素を標的とした治療開発を促進します。

RNA修飾機構の構成要素(ライター、イレーサー、リーダー)を標的とする手法が、疾患治療戦略として探求されています。たとえば、m6A脱メチル化酵素であるFTO阻害剤はがん治療において有望視されており、一方、mRNAワクチンにおける修飾ヌクレオチドは安定性と翻訳効率を高めます。

全体として、現在の研究は、「エピトランスクリプトームコード」の解読、RNA修飾の生体内精密操作のためのツールの開発、およびncRNAにおける修飾の探索に重点を置いています。シングルセルエピトランスクリプトミクスは、細胞タイプに特異的なRNA修飾パターンとその機能的影響を明らかにしつつあります。新興技術であるマルチオミクス統合は、エピゲノムデータとトランスクリプトミクス、プロテオミクス、メタボロミクスをCUT&RUNやHi-C統合などの技術を用いて組み合わせ、細胞機能の包括的な視点を提供します。これらのアプローチにより、複雑な疾患における包括的な経路解析とバイオマーカー発見が可能となります。

世代間継承

世代間継承とは、DNA配列の変化とは独立して、環境によって誘発されたエピジェネティックな変化が複数世代にわたって伝達される現象を指します。この現象は植物や動物で観察されており、ある世代が経験した環境への曝露が、その後の世代の健康と発達に影響を与える可能性があることを示唆しています。しかしながら、このプロセスが人間における程度と意義を検証することは困難です。

世代を超えたエピジェネティック遺伝の例としては、オランダ飢餓の冬(1944~1945)が挙げられます。ここでは、オランダで飢饉に晒された個人において、DNAメチル化パターンの変化と代謝リスクの増加が、その後の世代で観察されました。動物実験では、内分泌かく乱物質(ビンクロゾリンなど)が生殖、行動、疾病感受性に及ぼす世代を超えた影響の例も示されています。一方、人間においては、父親の喫煙や母親のストレスが子孫のエピジェネティックな変化と関連していることが明らかになっています。

世代を超えたエピジェネティックな遺伝の基盤となるメカニズムは完全には解明されていないものの、曝露を受けた個人の子孫において肥満、糖尿病、心血管疾患などの疾患リスクプロファイルを高める影響があることから、この分野は現在も活発な研究対象となっています。世代を超えた影響を理解することは、有害な環境要因への曝露を減らす政策立案にも役立ちます。特に発達の重要な時期(妊娠期間など)における曝露の低減が重要となります。

エピジェネティック編集とCRISPRベースの技術

CRISPR-Cas9技術の登場は遺伝子工学に革命をもたらし、そのエピジェネティクスへの応用も例外ではありません。エピジェネティック編集は、DNA配列を変更することなくエピジェネティックマーカーを修飾する技術であり、遺伝子調節の研究や新しい治療法の開発に強力なツールを提供します。

CRISPR-Cas9システムは、エピジェネティックなエフェクタードメインと融合した触媒作用のないCas9(dCas9)を特定のゲノム遺伝子座に誘導するために、ガイドRNA(gRNA)を採用しています。主要なエフェクタードメインには、DNMT(DNMT3Aなど)、DNA脱メチル化酵素(TET1など)、ヒストン修飾酵素(p300、HDACsなど)、そしてクロマチンリモデラーが含まれ、エピジェネティック修飾の正確な付加または除去を可能にします。

CRISPR-Cas9技術 は、エンハンサーやプロモーターなどの調節要素を標的とすることで遺伝子発現の選択的活性化または抑制を可能にし、研究者は特定のエピジェネティックマークが遺伝子調節、細胞分化、疾患における因果的役割を直接検証できるようにします。さらに、細胞分裂、発生、およびエピジェネティックな調節異常によって駆動される疾患モデルの作成におけるエピジェネティックな遺伝の検討を可能にします。

治療への応用には、がんや高コレステロール血症などにおいて、疾患を引き起こす遺伝子(がん遺伝子、ウイルス遺伝子)をサイレンシングし、有益なサイレンシングされた遺伝子(腫瘍抑制遺伝子)を再活性化することが含まれる。このアプローチは、オフターゲット効果を最小限に抑えた、高度に個別化された治療の可能性を秘めており、再生医療の細胞リプログラミングへの応用も可能です。CRISPRベースのエピゲノム編集の主な利点には、高い標的精度、交換可能なエフェクタードメインによる汎用性、および遺伝子編集と比較した変異原性リスクの低減などがあります。

この技術を推進するには、オフターゲットの影響を最小限に抑えるために、Casバリアントの開発と最適化されたgRNA設計が必要となります。さらに、多重標的化により複雑な調節ネットワークの調査が可能となり、改善された送達方法(ウイルスベクター、ナノ粒子)により臨床応用が促進されます。この分野における新興技術には、特にエピジェネティックエフェクター(DNMTs、TETs、HDACs)と融合したCRISPR/dCas9ベースのシステムなどのエピゲノム編集ツールが含まれます。代替プラットフォームとしては、遺伝子座特異的な標的化のためのTALE549およびジンクフィンガータンパク質などがあります。

シングルセルエピゲノミクス

シングルセルエピゲノミクス技術により、個々の細胞レベルでのエピジェネティック修飾のプロファイリングが可能になります。これは細胞の多様性と機能に関する前例のない知見を提供し、何百万もの細胞にわたる平均的なエピジェネティックマーカーを調べる従来のバルクシーケンス手法の欠点を克服するものです。

シングルセルATAC-seq(転移酵素可及性クロマチン解析法)やシングルセルChIP-seq(クロマチン免疫沈降シーケンス)といった技術は、個々の細胞におけるクロマチンアクセシビリティやヒストン修飾を解析する手法として、この潮流の最先端に位置しています。応用例には、胚発生、細胞および組織の分化、細胞運命の決定、免疫システムの異質性におけるエピジェネティックなランドスケープのマッピングが含まれます。

がん研究において、シングルセルエピゲノミクスは、クローン進化、薬剤耐性、転移に関連する腫瘍内エピジェネティック不均一性を明らかにすることができます。この技術はまた、神経発達、神経変性、および免疫細胞分化におけるエピジェネティックな変化を解明するために用いられ、自己免疫疾患や免疫療法の反応に関する理解を深めています。

今後の方向性としては、空間トランスクリプトミクスとの統合、細胞プロセスや環境刺激に応答するエピジェネティックマーカーの時間的プロファイリング、ならびにバイオマーカー同定や個別化医療への臨床応用などが挙げられます。

空間的エピゲノミクス

空間エピゲノミクスは、エピジェネティック修飾の研究と組織内の空間的コンテキストを組み合わせる最先端の技術です。このアプローチは、シングルセルエピゲノミクスと組織学を結びつけ、組織領域間でのエピジェネティックな調節の変化と、健康と疾病における細胞の組織化、機能、およびコミュニケーションへの影響を明らかにします。

応用例には、エピジェネティックな変化に導かれた器官形成過程における組織パターニングマッピング、転移や薬剤耐性を駆動する可能性のある腫瘍内(中心部対浸潤辺縁)の空間的に異なるエピジェネティックな特徴の同定、神経発達、可塑性、神経変性疾患に関する知見を提供する脳組織や細胞タイプにおける領域特異的なエピジェネティックな変化の特性化、免疫細胞ニッチ全体におけるエピジェネティックな調節の理解、そして組織ミクロ環境におけるエピジェネティックな状態の影響が含まれます。

健康と病気におけるエピジェネティクス

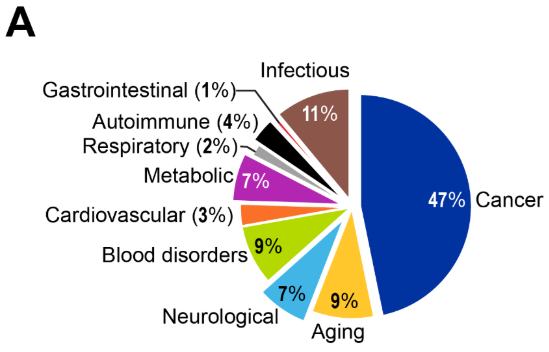

エピジェネティック修飾は、特定の遺伝子群を活性化またはサイレンシングすることで、胚の発生と細胞運命の決定を導きます。これらのプロセスの調節異常は数多くの病理に影響を及ぼし、がんが研究対象の主要な疾患領域であった一方で、他の疾患におけるエピジェネティクスの役割も研究されつつあります。

がん

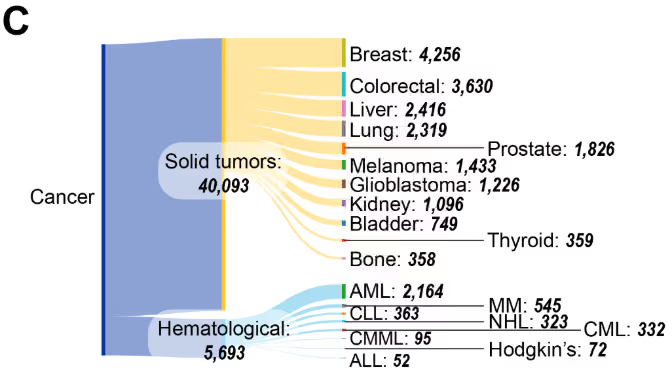

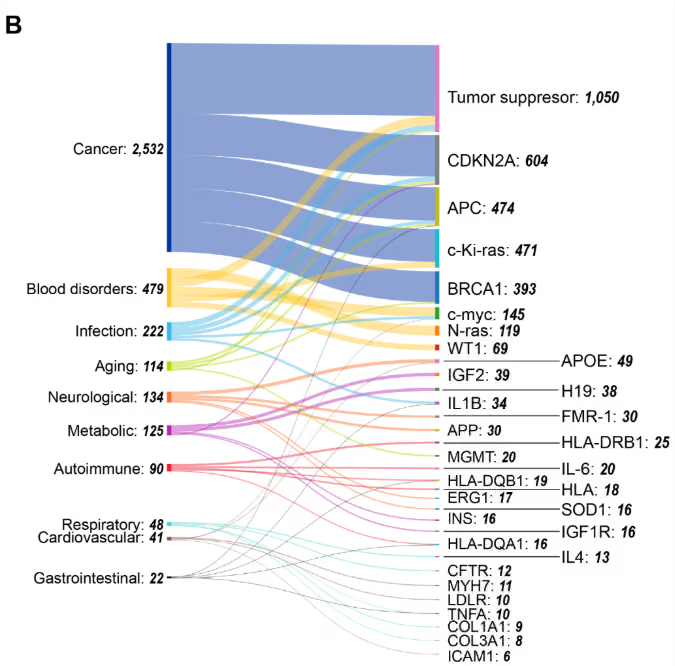

遺伝子の変異は長年、がんの原因因子として認識されてきましたが、現在ではエピジェネティックな変化もまた、腫瘍形成において同等に重要な役割を果たしていると理解されています。研究動向を見ると、がん研究が全文献の47%を占める圧倒的な存在感を示しており、この分野の成熟度と臨床応用における成功を反映しています(図4参照)。

固形腫瘍が圧倒的多数を占める文献において(図4C)、乳がん、大腸がん、肝がん、そして肺がんが研究活動の中心となっています。血液悪性腫瘍の中では、急性骨髄性白血病 (AML) が最も多く、次いで慢性リンパ性白血病 (CLL)、多発性骨髄腫(MM)が続いています。このCASコンテンツコレクションからの出版データに基づく本分布は、米国FDA承認のエピジェネティック療法と一致しており、AMLの治療に用いられるアザシチジンおよびデシタビン、ならびに皮膚性T細胞リンパ腫治療に用いられるボリノスタットを含む、これらの悪性腫瘍を標的とする治療法を対象としています。

がんにおけるエピジェネティックな調節には、主に3つのメカニズムが関与しています。

- DNAメチル化:プロモーター領域の過剰メチル化はしばしば腫瘍抑制遺伝子のサイレンシングにつながる一方で、ゲノム全体の低メチル化はがん遺伝子を活性化し、ゲノムの不安定性を促進します。

- ヒストン修飾:ヒストンのアセチル化、メチル化、リン酸化の変化は、クロマチン構造と遺伝子発現を変化させます。

- ncRNA:miRNAの調節異常(miR-21の過剰発現など)は、腫瘍抑制因子や癌遺伝子を標的とすることにより、癌の進行を促進する可能性があります。

図5に示された遺伝子-エピジェネティック機構の共起ヒートマップは、明確なパターンを示唆しています。たとえば、DNAメチル化の優位性は、重要なエピジェネティックなメカニズムとしての役割を反映しています。クロマチンリモデリングは、ほとんどの遺伝子間で共起が最小限であることから、遺伝子固有の調節ではなく、より広範な構造変化における役割を示唆しています。ncRNAおよびヒストン修飾に関連する文献は、DNAメチル化とクロマチンリモデリングという両極端の中間に位置しています。

遺伝子と疾患の共発生に関する我々の分析(図5B)は、腫瘍抑制遺伝子が最も高い連結性を示すことで、がんの中核的な位置付けを明らかにしています。複数のがん種で高い共発生率を示すその他の遺伝子には、CDKN2Aがあり、次いでAPC、c-Ki-ras(KRAS325)が続きます。このパターンは、これらの遺伝子が多様な悪性腫瘍においてメチル化を介したサイレンシングを受けるエピジェネティックなハブとしての役割を反映しています。

エピジェネティッククロックと加齢に伴う疾患

エピジェネティッククロックは、DNAメチル化パターンに基づいて生物学的年齢を予測する計算モデルを用いた画期的な概念です。それらは、個人の生物学的年齢と暦年齢の間に生じる不一致を明らかにし、加齢プロセスや生活習慣・環境要因の影響に関する知見を提供します。これらのモデルは、DNAメチル化における予測可能な加齢に伴う変化を利用しており、特定のゲノム領域が再現性のあるパターンで過メチル化または低メチル化される現象です。

第一世代のエピジェネティッククロックであるホルバスクロックは、2013年にSteve Horvath氏によって開発され、複数の組織および細胞タイプにわたる353個のCpGサイトからのDNAメチル化データを用いて生物学的年齢を推定します。同年に開発されたハンナムクロックは、主に血液中に存在する71のCpGサイトを利用します。GrimAgeやPhenoAgeのような最近のクロックは、精度向上と死亡率・疾患リスク予測のために追加のバイオマーカー(血漿タンパク質など)を組み込んでいます。

長寿研究において、100歳以上の人々や特に長寿な人々は、エピジェネティックな老化が遅い傾向を示し、健康的な老化を促進する遺伝的および環境的要因の手がかりを提供しています。現在の研究では、セノリチクスおよびエピジェネティックな調節因子標的化化合物による可逆性が探求されています。

図4Aに示す研究文献の傾向から、疾患と加齢を明示的に言及するエピジェネティクス研究において加齢が占める割合は9%であり、がん研究(47%)より著しく小さいものの、2010年から2024年にかけて着実な増加を示していることがわかります。特に2019年以降は顕著な増加傾向が認められます(図4B)。この割合は、がん応用が支配的な広範なエピジェネティクス領域において、加齢研究が専門的でありながらも拡大しつつある役割を反映しています。

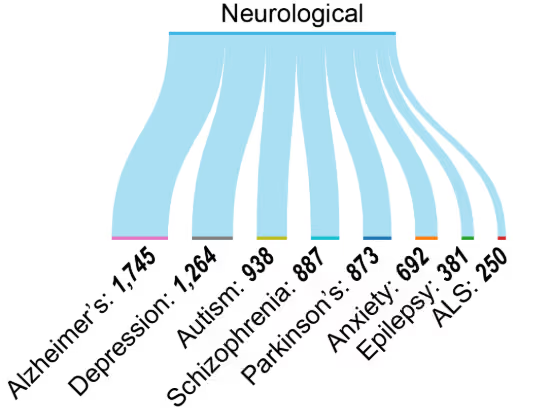

神経変性疾患

エピジェネティック修飾は、アルツハイマー病、パーキンソン病、ALSなどの神経変性疾患や、うつ病や統合失調症などの精神疾患と関連しています(図6)。豊富な研究成果は、神経精神疾患および神経変性疾患におけるエピジェネティックなメカニズムへの認識の高まりを反映しています(図4A参照)。

エピジェネティックな変化は、アルツハイマー病におけるアミロイドβ(Aβ)産生およびタウリン酸化に関与する遺伝子に影響を及ぼし、miR-29352やmiR-34354などのマイクロRNAの調節異常が認知機能低下と関連しています。パーキンソン病では、ミトコンドリア機能遺伝子(PINK1355など)およびα-シヌクレイン凝集経路においてエピジェネティックな変化が認められます。パーキンソン病モデルではヒストンアセチル化とDNAメチル化パターンが乱れ、神経細胞の生存に影響を及ぼします。

自閉症スペクトラム障害では、異常なDNAメチル化やヒストン修飾を介したシナプス関連遺伝子(SHANK3360など)の調節異常が認められ、動物モデルではバルプロ酸の胎内曝露などの環境要因がエピジェネティックな変化を誘導することが示されています。てんかんにおいては、エピジェネティックなメカニズムがイオンチャネル遺伝子とシナプス可塑性遺伝子を調節し、発作感受性に寄与しており、ヒストン修飾とmiRNAの異常発現が観察されます。神経発達障害は、メチルCpG結合タンパク質をコードするMECP2遺伝子の変異がレット症候群を引き起こし、脆弱X症候群ではFMR1遺伝子の過剰メチル化が生じるように、エピジェネティックな調節が極めて重要であることを示す好例です。

エピジェネティックな変化は神経疾患のバイオマーカーとしてますます認識されてつつあります。BDNF372やCOMT374などの遺伝子のメチル化パターンは認知機能や精神疾患と関連しており、一方、特定のヒストン修飾(H3K27me3など)は神経変性における遺伝子調節ネットワークと関連しています。循環型miRNA、特にmiR-132376とmiR-124378は、それぞれアルツハイマー病およびパーキンソン病の非侵襲的バイオマーカーとしての可能性を示しており、早期発見と治療モニタリングの可能性を秘めています。

心血管疾患

エピジェネティックなメカニズムはさまざまな心血管疾患の病因に寄与していますが、文献データの分析によれば、がんと比較して研究関心度は低いことが示唆されています(図4A参照)。たとえば、アテローム性動脈硬化症においては、DNAメチル化とヒストン修飾が炎症、脂質代謝、および内皮機能に関与する遺伝子を調節します。炎症誘発性遺伝子(IL-6384など)の低メチル化と抗炎症誘発性遺伝子(PPARγ385など)の高メチル化がプラーク形成を促進します。

血管緊張とナトリウム恒常性を調節する遺伝子におけるエピジェネティックな変化は高血圧に寄与する一方で、高塩分食やストレスなどの環境因子はこれらのエピジェネティックな変化を誘発する可能性があります。イオンチャネル遺伝子(SCN5AおよびKCNQ1392)のエピジェネティックな調節により、不整脈が発生しやすくなる可能性があります。同様に、エピジェネティック修飾は肥大や線維症を含む病的な心臓再形成を促進します。DNAメチル化、ヒストン修飾、そしてmiRNAはこれらのプロセスの主要な調節因子です。虚血性心疾患および脳卒中において、DNAメチル化とヒストン修飾により、細胞生存、ストレス反応、炎症経路を調節する遺伝子の発現が変化します。

神経疾患と同様に、これらの変化はバイオマーカーとしてますます記録されています。F2RL3400やAHRR401などの遺伝子のメチル化パターンは、心血管リスクおよび転帰と関連しています。特定のヒストン修飾は、心不全およびアテローム性動脈硬化における遺伝子調節ネットワークに関連しています。循環miRNA は、急性心筋梗塞および心不全のバイオマーカーとして用いられます。

代謝障害

エピジェネティック修飾は、インスリン感受性や脂肪蓄積、ならびに代謝性疾患における炎症に関与する遺伝子の発現を調節します。食事や運動などの環境因子は持続的なエピジェネティックな変化を誘発し、インスリン抵抗性や代謝機能障害に寄与します。

代謝性疾患は、エピジェネティクス研究のかなりの割合を占めており(図4A参照)、この分野では肥満研究と2型糖尿病が主流となっています。代謝疾患のグローバルな流行と、代謝機能障害に対するエピジェネティックな要因の関与への理解が深まっていることが、大量の文献に反映されています。代謝エピジェネティクス研究の着実だが緩やかな成長は、神経疾患や血液疾患の研究動向(図4B)と類似していますが、がん研究の急激な増加とは対照的であり、この分野には未開拓の潜在的可能性が依然として大きいことを示唆しています。

以下の点において、エピジェネティクスが重要な役割を果たしていることがわかっています。

- 肥満:DNAメチル化およびヒストン修飾が、脂肪分化、食欲調節、エネルギー消費に関連する遺伝子を調節し、肥満および脂肪組織機能障害にmiRNAの調節不全が関連しています。DNAメチル化とヒストン修飾が脂肪形成、食欲調節、およびエネルギー消費遺伝子を調節し、調節不全のmiRNAが肥満および脂肪組織機能障害と関連しています。

- 2型糖尿病(T2D):膵臓β細胞、肝臓、および骨格筋におけるエピジェネティックな変化がインスリン産生と感受性に影響を与え、PPARGC1AおよびIRS1遺伝子のDNAメチル化が含まれます。

- 非アルコール性脂肪肝疾患(NAFLD):DNAメチル化とヒストン修飾は肝臓の脂質代謝と炎症を調節し、miRNAが疾患の進行に寄与します。

- メタボリックシンドローム:エピジェネティックな変化は、グルコース代謝、脂質代謝、および血圧調節に関連する遺伝子に影響を及ぼします。

- 心血管代謝疾患:エピジェネティックなメカニズムは、動脈硬化症や高血圧リスクに関連するFTO418やABCA1419などの遺伝子のDNAメチル化を介して、代謝異常と心血管合併症を関連付けます。

代謝性疾患のエピジェネティックなバイオマーカーには、T2DおよびNAFLDに関連するTXNIPおよびSREBF1遺伝子のメチル化パターン、代謝関連遺伝子調節ネットワークに関連する特定のヒストン修飾、ならびにT2Dおよび肥満のバイオマーカーとして機能するmiRNAが含まれます。これらのバイオマーカーは、代謝性疾患における早期発見、リスク層別化、および治療モニタリングを可能にします。

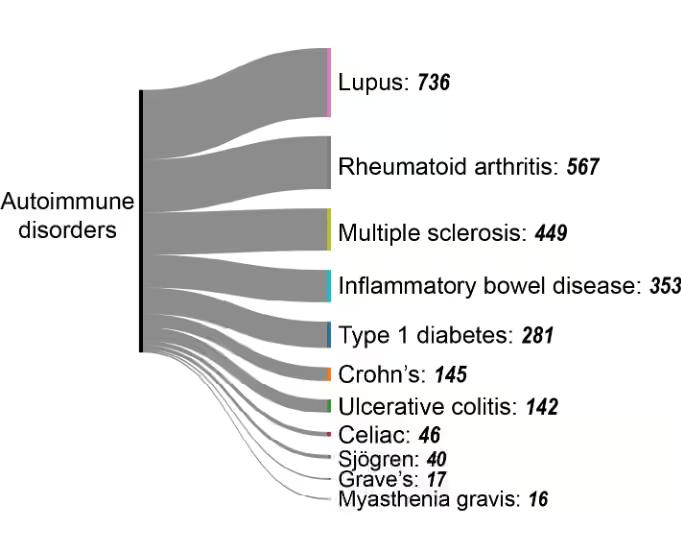

自己免疫疾患

免疫寛容遺伝子の異常メチル化は自己反応性T細胞を活性化し、自己免疫疾患を引き起こす可能性があります。臨床的重要性にもかかわらず、自己免疫疾患はエピジェネティクス研究においてわずかな割合を占めるに過ぎません(図4A参照)。2010年から2024年にかけての研究数は、がん研究における指数関数的増加(図4B)と比較すると、着実ではあるが限定的な伸びに留まっています。この研究のギャップは、自己免疫エピジェネティクスに関する調査の拡大に大きな可能性を示唆しています。

自己免疫疾患の中で、以下の特定の病態が主要な研究領域として浮上しています(図7)。

- 全身性エリテマトーデス(SLE)の病態形成と関連するmiRNAの調節異常。

- 関節リウマチ(RA)では、滑膜線維芽細胞および免疫細胞におけるDNAメチル化の変化が関節炎症を促進し、一方ヒストン修飾は炎症性サイトカイン産生を調節します。

- 多発性硬化症(MS)では、免疫調節およびミエリン破壊関連遺伝子に影響を及ぼすT細胞およびB細胞におけるエピジェネティックな変化が認められ、疾患進行に関連するmiRNAの異常発現が関連しています。

- 1型糖尿病(T1D)では、膵β細胞および免疫細胞におけるDNAメチル化とヒストン修飾が関与し、インスリン産生細胞の自己免疫性破壊に寄与しています。miRNA(miR-21、miR-34aなど)は病態形成に関係しています。

- クローン病や潰瘍性大腸炎などの炎症性腸疾患(IBD)は、腸管上皮細胞および免疫細胞においてエピジェネティックな変化を示し、miRNAの調節異常と関連とともに慢性炎症を引き起こします。

エピジェネティクス治療:エピ薬の臨床応用

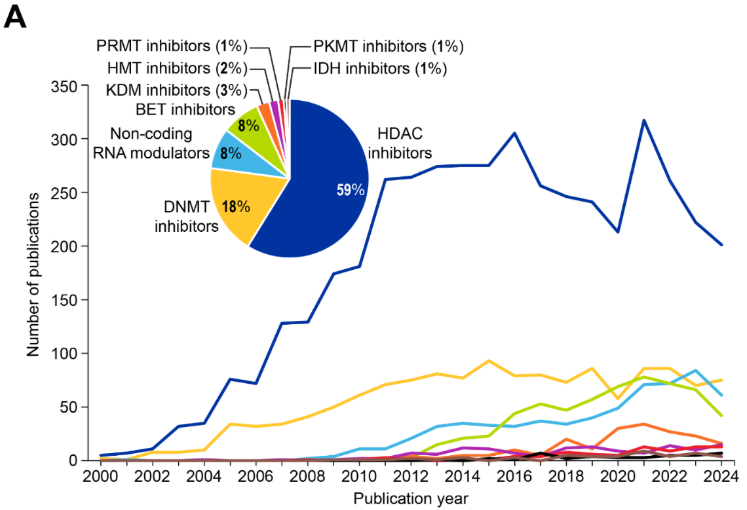

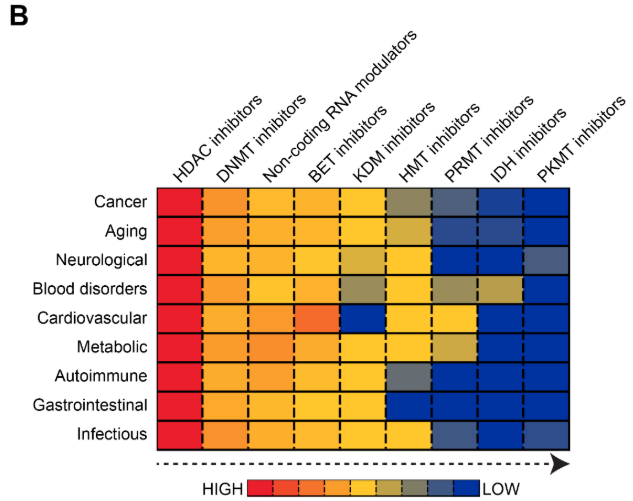

エピジェネティック薬(エピドラッグ)は、エピジェネティックな調節異常を特徴とする疾患において、異常なエピジェネティック修飾を逆転させ、正常な遺伝子発現を回復させます。治療領域(図8A参照)では、HDAC阻害剤が文献の59%を占めて優勢であり、次いでDNMT阻害剤(18%)、RNAモジュレーター(ncRNAモジュレーターが各8%)が続いています。

現行のエピ薬

- ヒストン脱アセチル化酵素(HDAC)阻害剤は、ヒストンからアセチル基が除去されるのを阻害し、緩和されたクロマチン構造と遺伝子発現の増加、特に腫瘍抑制遺伝子の発現を促進します。HDAC阻害剤は、転写因子やシャペロンタンパク質などの非ヒストンタンパク質にも影響を及ぼし、抗がん効果をさらに促進します。

- DNAメチル化酵素(DNMT)阻害剤は、関連する研究文献数において2番目に大きい薬剤クラスです。それらはDNMTをブロックし、それによってがんのサイレンシングされた腫瘍抑制遺伝子の再活性化を助けます。現在臨床使用が承認されているDNMT阻害剤は、アザシチジン(Vidaza®)とデシタビン(Dacogen®)です。これらはヌクレオシド類似体としてDNA複製中に組み込まれ、不可逆的にDNMTに結合し、メチル化を阻害します。

- ncRNAモジュレータは、miRNAやlncRNAを標的として遺伝子調節に影響を及ぼします。RNAモジュレータは、特に2018年以降急速に成長しているカテゴリーです(図8A)。miRNAやlncRNAが精密医療における薬理学的対象として認識されていることを反映しています。

- ブロモドメインおよび末端外ドメイン(BET)阻害剤は、BETタンパク質のアセチル化ヒストンへの結合を阻害し、がん遺伝子の転写活性化を阻害します。BETタンパク質(BRD2、BRD3、BRD4など)は、ヒストン上のアセチル化リジンの認識と結合に関与し、エピジェネティックマーカーの「リーダー」として機能します。

- ヒストンリジン脱メチル化酵素(KDM)阻害剤は、リシン脱メチル化酵素(LSD)やJumonjiドメイン含有(JmjC)ファミリーに属するN-メチルリジン脱メチル化酵素群を阻害します。今のところ承認されているKDM阻害剤はありませんが、KDM4 阻害剤(zavondemstat)が現在臨床試験中であり、さらなる開発に向けた研究が進められています。

- ヒストンメチル化酵素(HMT)阻害剤は、ヒストンタンパク質上の特定のリジンまたはアルギニン残基にメチル基を付加する酵素を標的とし、特定のヒストンやメチル化部位に応じて遺伝子発現を活性化または抑制します。

- タンパク質アルギニンメチル化酵素(PRMT)阻害剤は、タンパク質にメチル基を付加し遺伝子発現や細胞プロセスに影響を与える酵素であるタンパク質アルギニンメチル化酵素を標的とします。HMT阻害剤やPRMT・PKMT阻害剤などのタンパク質メチル化酵素阻害剤はまだ開発の初期段階ですが、KDM阻害剤は新たな治療の可能性を示唆しています。

- イソクエン酸デヒドロゲナーゼ(IDH)阻害剤は、腫瘍代謝産物である2-ヒドロキシグルタル酸を生成するIDH1やIDH2などの変異型IDH酵素を標的とします。これらの酵素はDNAの過剰メチル化を引き起こし、TETタンパク質やヒストン脱メチル化酵素などのエピジェネティックな調節に関与する酵素を阻害することで、細胞内に蓄積して細胞分化を阻害します。

- ゼステホモログ2(EZH2)エンハンサー阻害剤は、特定のHMT阻害剤として機能し、H3K27me3レベルを低下させ、サイレンシングされた腫瘍抑制遺伝子を再活性化します。これにより、特にEZH2変異または過剰発現のがんにおいて、正常な細胞分化を回復し、腫瘍の成長を抑制できます。

- 二重作用型もしくは多機能エピジェネティック調節剤は、複数のエピジェネティック経路を標的とするメカニズムを組み合わせたものです。これらの薬剤は、複雑な疾患における治療効果を高める可能性があります。

共起分析

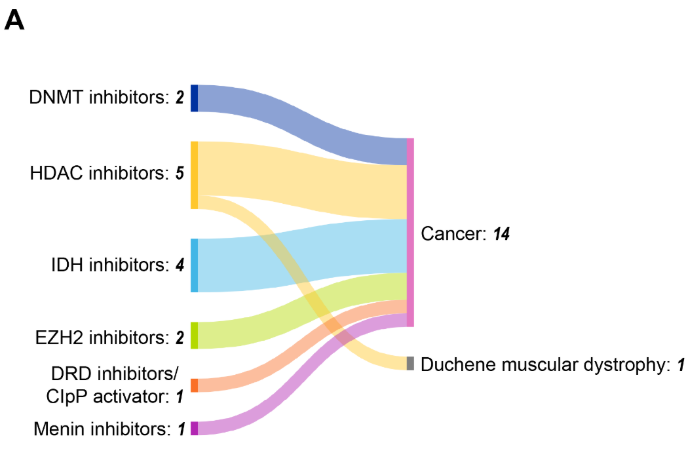

エピジェネティック治療薬の臨床状況は規制面での成功を示しており、主要なエピジェネティック調節因子を標的とする113の薬剤が米国FDAの承認を得ています(図9参照)。

HDAC阻害剤は5つの承認でトップを占め、血液悪性腫瘍が主要な治療適応領域であり、承認された15の適応症のうち12を占めています。この集中は、血液がんのエピジェネティック調節異常に対する感受性、および固形腫瘍と比較した血液学的標的へのアクセス可能性を反映しています。

DNMT阻害剤であるアザシチジン(2004年)およびデシタビン(2006年)は、骨髄異形成症候群およびAMLにおけるDNAメチル化を標的とする最初の承認されたエピジェネティック薬の一つであり、DNAメチル化を標的とする概念実証を確立しました。ボリノスタット、ロミデプシン、ベリノスタットなどのHDAC阻害剤は、複数の血液悪性腫瘍に対して有効性を示し、ヒストン修飾が治療標的として有効であることを実証しています。

臨床試験中のエピジェネティック薬

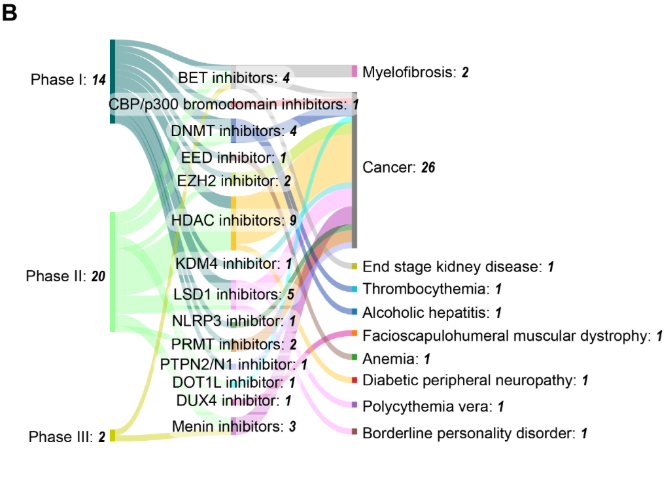

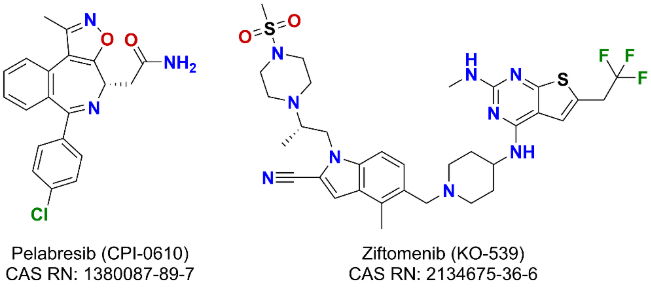

臨床試験におけるエピジェネティック薬の動向は、過去25年間で劇的に拡大し、clinicaltrials.govには約2,200件の試験が登録されています(図10参照)。2000年の1件の試験から2024年には年間200件近くの臨床試験へと持続的な増加が見られ、規制上の節目や市場動向を反映した顕著な変動が認められます。アザシチジンが2004年に米国FDAの承認を得て以降、臨床試験活動は増減を繰り返しながらも全体として上昇傾向を示しました。この成長パターンは、定期的な統合段階にもかかわらず、製薬投資が持続していることを示唆しています。

治療エピジェネティック臨床試験のフェーズ分布に関する分析によると、第II相試験が57%で最多を占め、次いで第I相(32%)、第III相(9%)となっています。この分布は医薬品開発において典型的なものであり、エピジェネティック医薬品開発における高い淘汰率と、多くの併用戦略の探索的性質を反映しています。注目すべきは、試験の62%が米国FDA承認薬を対象としており、初期適応症を超えた適応拡大の取り組みや併用療法の探索が広く行われていることを示唆されていることです。残りの38%の臨床試験は、新規/未承認の新薬を対象とするものです。

臨床開発パイプラインは、3つのフェーズにわたる36件の試験が進行中であり、活発な活動を示唆しています。第II相試験が最多を占め(23 件)、DNMT阻害剤とHDAC阻害剤はそれぞれ4件と11件の試験で臨床現場での存在感を維持して持しています。DNMTやHDAC阻害剤以外にも多様化が進んでおり、LSD1、BET、メニン阻害薬の研究が活発化しています(図9B参照)。この分布は、確立された標的の継続的な最適化と、新規エピジェネティック調節因子への拡大の両方を示唆しています。がん領域の臨床試験が36件中26件と依然として主流を占める一方、血小板増加症、アルコール性肝炎、骨髄線維症、糖尿病性末梢神経障害など非がん領域への有望な多様化がデータから示唆されています。

臨床開発段階の有望な薬剤

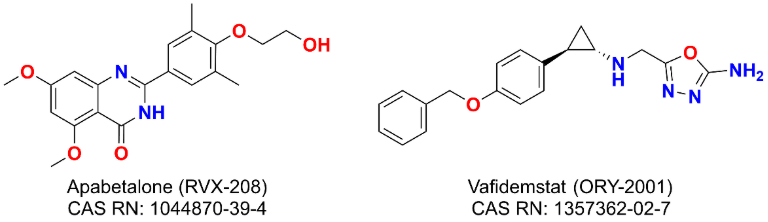

開発中のさまざまな薬剤の中で、がんやその他の疾患に対して有望なものがいくつか注目されています。

- 腫瘍治療薬

- ペラブレシブ(CPI-0610)は先進的なBET阻害剤として、骨髄線維症に対する第III相試験段階に到達しました。

- メニン-KMT2Aタンパク質間相互作用の選択的小分子阻害剤であるジフトメニブ(KO-539)は、2024年3月に再発性または難治性のNPM1変異型AMLに対する米国FDAの画期的治療薬の指定を受けました。

- 非腫瘍治療薬

- アパベタロン(RVX-208)は、BD2ドメインを標的とする選択的BET阻害剤であり、現在末期腎病を対象とした第I/II相試験の段階にあります。

- ラルスコステロール(DUR-928)は、内因性の硫酸化オキシステロールであり、ファースト・イン・クラスのエピジェネティック制御薬として、現在アルコール性肝炎を対象とした第II相臨床試験が進行中です。

- Vafidemstat (ORY-2001) は選択的 LSD1 阻害剤であり、現在境界性人格障害に対する第 II 相臨床試験で評価中です。

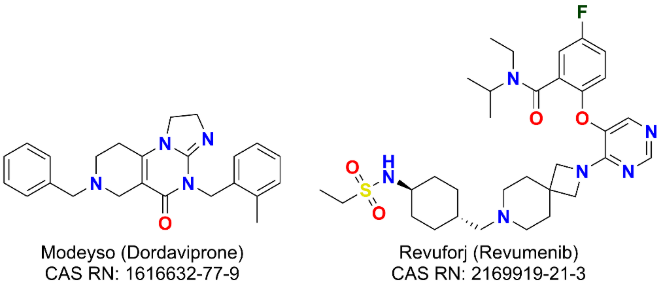

- 最近承認されたエージェント:

- Modeyso(ドルダビプロン)は2025年8月、1歳以上のH3 K27M変異陽性びまん性正中線神経膠腫(DMG)患者を対象に、米国FDAより迅速承認を取得しました。

- Revuforj(レブメニブ)は、成人および小児患者を対象とした再発/難治性のKMT2A再構成AMLについて、2024年11月に米国食品医薬品局の承認を取得しました。

個別化医療におけるエピジェネティクス

エピジェネティックデータの統合は、特に複雑な疾患に対する高精度の診断ツール、予後マーカー、および治療アプローチの開発を支援します。前述のように、DNMT 阻害剤や HDAC 阻害剤などのエピドラッグは臨床的に確立されており、開発が続けられています。エピジェネティック医薬品を化学療法および免疫療法と統合した併用療法も治療効果を高めており、個別化治療アプローチにおける重要な進歩を示しています。

エピジェネティクスにおけるもう一つの重要な進展は、これらの修飾を組織特異的なバイオマーカーとして活用することです。疾患特異的なパターンの例としては、がんにおける癌抑制遺伝子の過剰メチル化や、アルツハイマー病およびパーキンソン病患者に認められる異常なメチル化およびヒストン修飾などが挙げられます。

これらのエピジェネティックバイオマーカーの同定により、早期の疾患発見と診断が可能になります。例えば、血液やその他の体液中のがん特異的DNAメチル化パターンを検出するために使用される液体生検を通じて、非侵襲的な診断とモニタリングが可能になります。また、母体血液中のエピジェネティックマーカーを用いた出生前検査により胎児の健康状態を評価することができます。予後エピジェネティックマーカーは、病気の結果と治療への反応を予測することができます。たとえば、メチル化の状態は一部のがんにおける転帰や転移の可能性を予測し、精神疾患におけるエピジェネティックな変化は薬物反応を予測する可能性があります。

エピジェネティックバイオマーカーの臨床応用

エピジェネティックバイオマーカーは、病気の診断、予後、治療上の意思決定において重要です。エピジェネティックバイオマーカーに特化したCASコンテンツのコレクションの出版物を分析したところ、2008〜2009年頃から急激な増加が見られ、一部の期間(2015〜2017年と2023〜2024年)で横ばいになったことがわかりました(図11を参照)。

四つの主要なエピジェネティック機構の中で、DNAメチル化とncRNAが最もよく研究されており、DNAメチル化とncRNAバイオマーカーに関する出版物は2015年から2022年の間に倍増しました。一方、ヒストン修飾とクロマチンリモデリングはこの文脈では比較的研究が進んでいません。図11Bに見られるように、がんはエピジェネティックバイオマーカーに関連する出版物と最も共起しており、これは腫瘍形成におけるエピジェネティックな調節異常の確立された役割と、診断および予後におけるMGMT516やVIM517などのメチル化マーカーの臨床的有用性を反映しています。加齢研究が大きな割合を占めている事実は、近年のエピジェネティッククロック開発の進展や、それを用いた生物学的年齢評価への応用と致しています。

DNAメチル化バイオマーカー

異常なDNAメチル化パターンは疾患の特徴として機能し、特に腫瘍抑制因子の過剰メチル化は様々ながんの一般的なバイオマーカーとなっています。例えば、SEPT9メチル化は大腸内視鏡の代替として血液検出による非侵襲的な大腸がんスクリーニングを可能にします。膠芽腫において、MGMTプロモーター領域のメチル化はテモゾロミドへの治療反応性を予測する指標であり、高メチル化は予後の改善と関連しています。BRCA1メチル化は、乳がんと卵巣がんの増加、上昇のリスクに関連する診断および予後マーカーとして機能します。特筆すべきは、DNAメチル化が最も顕著にエピジェネティックバイオマーカー研究と共起していることで、これはその化学的な安定性、確立された検出方法論、そしてFDA承認のテストを通じた直接的な臨床応用によるものと考えられます。

ヒストン修飾バイオマーカー

ヒストン修飾はクロマチン構造や遺伝子発現に影響を与え、特定のヒストンマークは疾患状態と関連しています。図11Bで見られる比較的控えめなヒストン修飾の共起は、特にその動的な性質と治療介入への反応性を考えれば、未開拓の可能性を示唆しています。

ヒストンH4のアセチル化の喪失は特定のがんの予後不良を予測し、一方でヒストンH3のリジン27三メチル化(H3K27me3)はPRC2の機能不全を反映し、前立腺がんと膀胱がんで予後不良と相関します。ヒストンH3/H4のシトルリン化は、抗シトルリン化タンパク質抗体(ACPAs)の産生と関連しており、これは関節リウマチの特徴であり、診断とモニタリングを可能にします。

これらの有望な発見にもかかわらず、ヒストン修飾の非常に不安定な性質や、サンプル採取後数分以内に急速な信号消失を引き起こす酵素分解の感受性などの課題が残っています。現在のプロトコルでは、プロテアーゼ、脱アセチル化酵素、脱メチラーゼ阻害剤を含む特殊な保存緩衝液が必要であり、日常的な臨床導入が複雑になっています。

ncRNAバイオマーカー

miR-21529やmiR-155530などのmiRNAを含むncRNAは、さまざまな癌で過剰発現しており、体液を通じて診断および予後バイオマーカーとして機能します。エピジェネティックバイオマーカー研究とncRNAの共起が顕著であることは、低侵襲性バイオマーカーとしての循環miRNAおよびlncRNAへの関心が高まっていることを反映しています。

たとえば、miR-21の過剰発現は、乳がん、肺がん、結腸直腸がん全体の腫瘍の増殖、浸潤、転移、化学療法抵抗性に関連しています。miR-208aレベルの上昇は、急性心筋梗塞(心臓発作)のバイオマーカーとして機能します。HOTAIR lncRNAの過剰発現は、乳がん、結腸直腸がん、膵臓がんの転移や予後不良にも関連しています。

クロマチンリモデリングバイオマーカー

クロマチンリモデリングパターンは治療抵抗性を予測し、薬剤耐性のあるがん細胞におけるオープンクロマチン領域は治療失敗を予測するために使用されます。ヒストンの修飾と同様に、クロマチンリモデリングの共起が比較的低いことは、未開発の可能性を示唆しています。

全体として、エピジェネティックバイオマーカーの将来は、堅牢で高スループットの技術と統合的アプローチの開発にあります。マルチオミクスデータの統合(エピジェネティック、ゲノミック、トランスクリプトミック、プロテオミックデータの組み合わせ)により、バイオマーカーの発見と検証が向上します。体液中のエピジェネティックバイオマーカーの非侵襲的検出は、早期診断とモニタリングに革命をもたらすでしょう。

高度な計算ツールは、患者の層別化のための複雑なエピジェネティック特性の特定に役立つことが期待されています。たとえば、CRISPRベースのエピゲノム編集により、治療目的で疾患に関連するエピジェネティックマークを操作できるようになり、バイオマーカーを診断ツールから治療ツールに移行できる可能性があります。

医療におけるエピジェネティクスの倫理的、法的、社会的影響

エピジェネティクスは健康と病気に対する理解を変革する可能性を秘めていますが、同時に重大な倫理的、法的、社会的課題も引き起こします。これらの課題に対処するには、エピジェネティック研究の利点と個人の権利を保護し社会正義を促進する必要性とのバランスをとる積極的かつ協調的なアプローチが必要です。強力な倫理ガイドライン、法的保護、および患者・市民参画戦略を開発することにより、エピジェネティクスの力を活用して、潜在的な危害を最小限に抑えながら健康と幸福を向上させることができます。

倫理的配慮

- プライバシーと差別:エピジェネティック情報は、遺伝子データと同様、非常に個人的な情報であり、個人の健康状態、ライフスタイルの選択、環境への暴露に関するセンシティブな情報を明らかにする可能性があるため、強固なプライバシー保護が必要です。例えば、病気のリスクを予測するエピジェネティックマーカーは、保険料の値上げや保険適用の拒否といった健康保険会社による差別を可能にする恐れがあります。同様に、過去の行動からエピジェネティックな修飾を検出する能力は、遡及的な健康評価や雇用差別に関する懸念を引き起こします。

- 個人の責任と世代を超えた影響:関連して、エピジェネティック情報は、健康状態のより広範な社会的・環境的決定要因を無視し、個人の健康状態を個人の責任として帰属させる結果を招く可能性があります。環境要因によって誘発されたエピジェネティックな変化は、時に次世代へ受け継がれることがあります。これは、エピジェネティックマーカーを変化させる介入の長期的な結果に関する倫理的懸念を引き起こします。

法的要件

- 規制の監督:消費者に直接販売されるエピジェネティック検査キットの急増により、正確性、解釈、規制に関する懸念が生じています。法的枠組みは、これらの応用がエビデンスに基づき、倫理的に妥当なものであることを保証すると同時に、実証されていない技術の時期尚早な商業化を防ぐ必要があります。

- 責任と知的財産:環境への暴露に関連したエピジェネティックな修飾は、複雑な責任問題を引き起こします。例えば、毒素による害は雇用主、製造業者、政府のいずれかの責任であるべきでしょうか?親や第三者の過失、あるいは環境への曝露によって胎児に生じたエピジェネティックな害に対する潜在的な法的責任については、慎重な検討が必要です。エピジェネティック研究の商業化、例えばバイオマーカーや治療法は、特許や所有権に関する問題を引き起こし、革新とエピジェネティック技術への一般のアクセスの維持のバランスを必要とします。

社会的影響

- 公衆の理解と公平性:エピジェネティクスに対する公衆の理解が限られていることで、誤解や実証されていない治療法(例:「エピジェネティックダイエット」)による搾取が生じています。この問題に対処し、情報に基づいた意思決定を改善するためには、包括的な教育と充実した科学的コミュニケーションが不可欠です。環境曝露と疾病を関連付けるエピジェネティック研究は、特に高レベルの汚染物質や毒素に曝露された特定のコミュニティーや集団に対する偏見につながる可能性もあります。エピジェネティック治療への公平なアクセスを確保し、健康格差の悪化を防ぐには、社会経済的障壁に対処する意図的な政策介入が必要です。

- 実施戦略:効果的なガバナンスには、エピジェネティックデータの収集、使用、共有に関する明確な倫理指針、エピジェネティック情報特有の課題に対処する最新の法的枠組み、信頼とインフォームドコンセントを育む一般市民の関与、管轄区域を超えた一貫した基準を確保する国際協力が必要です。責任あるイノベーションを推進しながら強力な保護策を講じることで、社会はエピジェネティクスの変革の可能性を活用しながら、個人の権利を守り、健康の公平性を促進することができます。

エピジェネティクスの今後の方向性

エピジェネティクス研究の状況は過去10年間で目覚ましい変化を遂げ、分子生物学の専門分野から、人間の健康と治療介入に深く関わる主流の生物医学分野へと進化しました。エピジェネティクス研究の臨床応用は目覚ましい成果を上げており、15のFDA承認薬がエピジェネティック標的の治療的有効性を実証しています。複数の開発段階で進行中の36件の臨床試験は、エピジェネティック治療薬への持続的な投資と信頼を示しており、がんを超えた多様化が期待されています。現在、試験は代謝性疾患、神経疾患、炎症性疾患、希少疾患にまたがっています。

この変化は、食事、ストレス、毒素、ライフスタイルの選択などの環境因子が、世代を超えて影響を与える遺伝的なエピジェネティックな変化を引き起こすという認識の高まりを反映しています。環境曝露データと個々のエピジェネティックプロファイルを統合することで、パーソナライズされたリスク評価と介入戦略が可能となり、予防的かつ精密な医療アプローチへの根本的な転換を表しています。

エピジェネティクスの未来は明るく、生物学の理解を深め、人間の健康を改善する大きな可能性を秘めています。しかし、この可能性を実現するには、技術的な制限、倫理的な懸念、エピジェネティック制御の複雑さなど、大きな課題を克服する必要があります。学際的なコラボレーションを促進し、革新的な技術に投資し、倫理的および社会的影響に対処することで、エピジェネティクスの分野は画期的な発見を続け、それを有意義な臨床的および社会的利益に変換することができます。