A visão computacional, um campo da inteligência artificial (IA), permite que os computadores "vejam" e interpretem o mundo visual como os humanos fazem. Muito além do simples reconhecimento de imagens, a visão computacional envolve a compreensão do contexto, das relações e dos padrões presentes nos dados visuais. Isso é conseguido por meio de algoritmos sofisticados e técnicas de aprendizado profundo, como redes neurais convolucionais (CNNs) e Vision Transformers (ViT).

Essas ferramentas extraem informações significativas de entradas visuais, transformando dados brutos de pixels em uma compreensão semântica de alto nível. Desde carros autônomos e controle de qualidade industrial até imagens médicas e filtros de mídias sociais, a visão computacional está revolucionando todos os tipos de setores e aspectos da vida cotidiana. Na pesquisa científica, ela já está promovendo avanços transformadores em inúmeras disciplinas e, à medida que conjuntos de dados crescem e a tecnologia evolui, ela impulsionará ainda mais descobertas importantes.

Por que a visão computacional é importante para a consulta científica

Como a visão computacional difere do aprendizado de máquina (ML) e de outros subgrupos de IA/ML, e por que isso é importante para a ciência? Em termos simples, essa tecnologia permite que cientistas encontrem insights valiosos rapidamente em uma vasta variedade de dados visuais. Nas últimas décadas, vimos uma explosão de dados científicos, de terabytes de dados astronômicos a milhões de imagens de microscopia, a sequências genômicas completas e muito mais. Em geral, o volume de dados é impossível de analisar manualmente, e grande parte dele é baseada em imagens, não em texto.

Essa é uma diferença crucial entre a visão computacional e outros subcampos da inteligência artificial. Enquanto o Processamento de Linguagem Natural (PLN) analisa dados textuais sequenciais para mineração de literatura e extração de conhecimento, a visão computacional lida com dados espaciais de alta dimensão, permitindo a análise direta de observações experimentais, imagens de microscopia e leituras de sensores, onde as relações espaciais e os padrões visuais contêm a informação científica essencial.

Além disso, métodos tradicionais de aprendizado de máquina, como regressão, clusterização e classificação, utilizam conjuntos de dados pré-processados e com engenharia de atributos, enquanto a visão computacional moderna baseada em deep learning realiza aprendizado de ponta a ponta a partir de pixels brutos, extraindo automaticamente atributos relevantes e hierarquias espaciais que podem não ser evidentes para pesquisadores humanos. Essa distinção é fundamental em contextos científicos, pois destaca as limitações dos modelos tradicionais de aprendizado de máquina e os recursos superiores dos modelos de aprendizado profundo, especialmente para dados visuais ricos. Os modelos tradicionais de aprendizado de máquina frequentemente atingem um platô de desempenho ao lidar com conjuntos de dados complexos e não estruturados e podem ter dificuldade em capturar diferenças visuais sutis que os modelos de deep learning conseguem.

Outra abordagem comum de IA é a modelagem preditiva, que prevê resultados com base em dados anteriores. A visão computacional, por outro lado, descobre padrões e estruturas diretamente a partir de observações visuais brutas, muitas vezes revelando fenômenos antes não reconhecidos sem exigir hipóteses predefinidas ou recursos de entrada estruturados.

| Abordagem de IA | Tipo de dados primários | Principais Diferenças |

|---|---|---|

| Visão computacional (CV) | Imagens, vídeo, dados visuais e espaciais | Processa dados a partir de pixels brutos; extrai automaticamente recursos e hierarquias espaciais; pode analisar informações visuais multiescala (do molecular ao astronômico); permite análise direta de observações e leituras de sensores |

| Processamento de Linguagem Natural (NLP) | Texto, dados linguísticos sequenciais | Concentra-se em padrões linguísticos, sintaxe e semântica; é utilizada para mineração de literatura e extração de conhecimento de fontes escritas. |

| Aprendizado de máquina | Conjuntos de dados com características projetadas | Requer dados pré-processados em vez de entradas brutas; trabalha com conjuntos de dados específicos; depende de recursos definidos por humanos em vez de extração automática de recursos |

| Modelagem preditiva | Dados históricos/de séries temporais | Prevê resultados futuros com base em padrões passados; requer hipóteses predefinidas e dados estruturados; projeta tendências em vez de descobrir padrões. |

Essas inovações analisam conjuntos de dados imensos muito mais rápido do que humanos conseguiriam sozinhos. Isso se traduz em análise mais rápida de possíveis compostos de fármacos, controle de qualidade mais preciso em alimentos e produtos industriais e intervenções mais precoces na saúde das lavouras, para citar apenas algumas aplicações. A visão computacional abre novas possibilidades de insights e descobertas importantes em conjuntos de dados cada vez maiores e facilita monitoramento automatizado 24/7 e feedback experimental em tempo real em diversas disciplinas.

Casos de uso da visão computacional nas ciências

Embora o núcleo da tecnologia de visão computacional, principalmente CNNs e mecanismos de atenção, permaneça semelhante entre os campos científicos, sua implementação varia de acordo com o tipo de dados visuais analisados e os objetivos científicos relevantes. Por exemplo, analisar anomalias sutis nos tecidos em exames médicos requer um treinamento de modelo diferente do que processar dados de satélite que rastreiam índices de saúde de plantas em todo o espectro visual. Cada domínio exige pré-processamento, estratégias de treinamento e métricas de avaliação especializados, adaptados a desafios específicos do domínio, seja para detectar eventos raros, medir quantidades precisas ou interpretar relações espaciais complexas, ao mesmo tempo em que aproveita as mesmas arquiteturas subjacentes de visão computacional.

- Pesquisa farmacêutica: O exame de estruturas microscópicas, como moléculas e proteínas, é fundamental para a descoberta de medicamentos. A visão computacional é ideal para essas aplicações porque aplica estruturas de IA, como CNNs e ViT, a esses conjuntos de dados visuais especializados. Na análise de estruturas moleculares, a visão computacional agiliza o processo de determinação de estruturas cristalográficas ao interpretar padrões de difração de raios X e mapas de densidade eletrônica. Ele também identifica estruturas químicas a partir de dados espectroscópicos e desenhos moleculares.

Para o dobramento de proteínas e a biologia estrutural, a IA analisa imagens de microscopia crioeletrônica para reconstruir estruturas proteicas de alta resolução, valida previsões computacionais de dobramento como as do AlphaFold e observa mudanças conformacionais dinâmicas que ocorrem durante processos biológicos. Na histopatologia, a visão computacional facilita a detecção automatizada de câncer e a graduação tumoral a partir de amostras de tecido, realiza análises quantitativas de características celulares e biomarcadores e processa com precisão imagens de lâminas inteiras em gigapixels, muitas vezes superando patologistas humanos em precisão.

Aplicações de triagem de medicamentos empregam triagem de alto conteúdo para categorizar automaticamente as respostas celulares aos tratamentos, monitorar a dinâmica de células vivas em tempo real e avaliar modelos complexos de organoides 3D para testar a eficácia de medicamentos. Essas inúmeras aplicações na descoberta de medicamentos mostram o quão versátil a visão computacional pode ser como ferramenta científica, acelerando as descobertas em todo o espectro, do molecular ao tecidual, na pesquisa biomédica.

- Ciência dos materiais: Assim como na indústria farmacêutica, a ciência dos materiais exige a análise de moléculas microscópicas para garantir a consistência dos materiais, detectar falhas e confirmar que os pequenos cristais presentes em metais e outros materiais foram projetados adequadamente. Na identificação da estrutura cristalina, a visão computacional analisa com eficácia os padrões de difração de raios-X e elétrons, permitindo a rápida identificação das fases cristalinas, a determinação das orientações por meio da análise do padrão EBSD Kikuchi e o mapeamento dos limites dos grãos. A tecnologia completa essas tarefas em uma fração do tempo necessário para analisar os cristais manualmente.

Para detecção de defeitos, a visão computacional permite identificação de falhas em tempo real, desde deslocamentos em escala atômica capturados em imagens de microscopia eletrônica de transmissão (TEM) até defeitos de fabricação maiores observados em processos de soldagem e fundição. Essa tecnologia tem aplicações especializadas em inspeções de pastilhas semicondutoras e camadas de monitoramento na manufatura aditiva.

Os sistemas de visão computacional já estão perfeitamente integrados às linhas de produção para inspeções de superfície em tempo real, medições dimensionais e decisões automatizadas de aprovação/reprovação para controle de qualidade. Esses sistemas têm aplicações específicas em diversos setores, desde a detecção de defeitos na pintura automotiva até a inspeção de comprimidos farmacêuticos e a verificação da montagem de placas de circuito impresso.

- Química sintética: a visão computacional está transformando o campo da pesquisa e síntese química , introduzindo análises visuais automatizadas em diversas aplicações, incluindo monitoramento de reações, interpretação de diagramas e rastreamento de compostos. No monitoramento de reações, sistemas de visão computacional observam mudanças em tempo real na cor, na formação de cristais e nas separações de fases, ao mesmo tempo em que analisam padrões térmicos e sinais de fluorescência. Isso permite que eles identifiquem os pontos finais ideais da reação, detectem impurezas e evitem reações descontroladas.

Para a interpretação de diagramas químicos, a visão computacional facilita a conversão de estruturas moleculares desenhadas à mão em formatos legíveis por máquina. Também extrai estruturas químicas de patentes e literatura científica, e decompõe esquemas complexos de reação para coletar informações sobre rotas sintéticas, reagentes e condições para desenvolvimento de bancos de dados e planejamento retrosintético.

No que diz respeito ao acompanhamento da síntese de compostos, essa tecnologia se integra perfeitamente à automação de laboratório para supervisionar sínteses em múltiplas etapas, coordenar processos de purificação, gerenciar inventários químicos e possibilitar a triagem de alto rendimento de reações paralelas em placas de microtitulação. Esses avanços utilizam adaptações personalizadas de arquiteturas centrais de visão computacional para lidar com desafios específicos da indústria química, como manter a consistência da iluminação para uma análise de cores precisa, garantir a compatibilidade química dos sistemas de imagem e integrar dados espectroscópicos e de sensores para uma compreensão mais abrangente dos processos.

O impacto dessas tecnologias é profundo: reduzir tempos de otimização de reações de semanas para dias, eliminar a subjetividade da avaliação humana, permitir monitoramento remoto de processos perigosos e revelar padrões visuais sutis ligados a resultados sintéticos bem-sucedidos. Isso representa uma mudança significativa rumo à síntese química autônoma e baseada em dados, que tem grande potencial para acelerar a descoberta de fármacos e otimizar processos de fabricação por meio de análise visual sistemática de transformações moleculares.

- Biotecnologia: De células individuais a tecidos complexos, a pesquisa biológica envolve inúmeras fontes de dados baseadas em imagens, ideais para análise por visão computacional. O grande volume de células e os potenciais padrões morfológicos também dificultam a identificação manual de tendências ou anomalias, mas soluções baseadas em IA podem enfrentar esses desafios e fornecer feedback em tempo real.

Por exemplo, sistemas de visão computacional classificam automaticamente células e avaliam seus estados. Eles quantificam várias características morfológicas, como forma, características nucleares e organização citoplasmática. Além disso, esses sistemas podem acompanhar processos dinâmicos, como migração e divisão celular, e desempenham um papel crucial na triagem de alto conteúdo para descoberta de fármacos e análise fenotípica.

A integração da microscopia incorpora a fusão de dados de imagens multimodais e apresenta sistemas de aquisição automatizados que possuem amostragem inteligente e capacidades de triagem de alto rendimento. A análise em tempo real com controle por feedback e técnicas avançadas de processamento de imagens, como desconvolução e reconstrução 3D, aumenta a eficiência da pesquisa. Essas aplicações utilizam arquiteturas especializadas em IA, incluindo segmentação de instâncias para culturas celulares densamente povoadas, modelagem temporal para análise de séries temporais e aprendizado em poucos tiros para se adaptar a novas condições experimentais. Eles também abordam considerações biológicas, como o gerenciamento da fototoxicidade e a garantia do controle ambiental.

- Alimentos e bens de consumo: A visão computacional está transformando a segurança alimentar e o controle de qualidade com sofisticados sistemas de inspeção automatizados que mantêm a integridade do produto desde a matéria-prima até a embalagem final. A inspeção visual é, obviamente, uma área em que essa tecnologia se destaca, e ela pode realizar avaliações em tempo real da qualidade de superfície e identificar defeitos, contaminação e até níveis de maturação em diversos alimentos.

A visão computacional também monitora aspectos da qualidade do processamento, como níveis de cozimento e consistência da textura, em velocidades de produção superiores a 1.000 itens por minuto. O equipamento realiza a análise de ingredientes inspecionando as matérias-primas, confirmando a mistura adequada e a distribuição do tamanho das partículas, e garantindo a adição correta dos ingredientes. Essa análise visual detalhada é inovadora para o controle de alérgenos, evitando contaminação e minimizando o desperdício. A tecnologia também oferece benefícios semelhantes para a verificação da segurança de embalagens, como garantir que os rótulos sejam legíveis e que as embalagens estejam corretamente preenchidas e seladas.

- Agricultura e ciências ambientais: a visão computacional fornece análises detalhadas de imagens de satélite e drones, que são cruciais para o monitoramento ambiental e a pesquisa ecológica. No âmbito do monitoramento da saúde das culturas, sistemas baseados em inteligência artificial analisam imagens multiespectrais para calcular índices de vegetação, como o índice de vegetação por diferença normalizada (NDVI), que quantifica o grau de verdor, a densidade e a produtividade da vegetação. Eles também criam mapas de agricultura de precisão para aplicações em taxa variável e preveem rendimentos por meio do monitoramento detalhado do desenvolvimento das culturas ao longo do tempo.

A visão computacional também aprimora o rastreamento da poluição, como a avaliação da qualidade do ar por meio da detecção de partículas e emissões, o monitoramento da qualidade da água com ferramentas para identificar florações de algas e derramamentos de petróleo, a garantia da conformidade industrial e a realização de estudos ambientais urbanos. Na identificação de espécies para estudos ecológicos, sistemas automatizados são empregados para monitorar populações de animais selvagens e rastrear migrações. Esses sistemas também avaliam ecossistemas marinhos detectando baleias e monitorando a saúde dos recifes de coral, mapeiam a biodiversidade para esforços de conservação e analisam a ecologia florestal para classificação de espécies de árvores e tendências fenológicas.

Essas aplicações usam tecnologias de ponta, como fusão de dados multissensores, que combina dados ópticos, de radar e hiperespectrais. Elas empregam análises temporais para detecção de mudanças e monitoramento de tendências, enquanto o processamento em alta resolução aproveita redes de aprendizado profundo treinadas em extensos conjuntos de dados de sensoriamento remoto. A integração de constelações de satélites e enxames de drones garante ampla cobertura, e plataformas de computação em nuvem facilitam o processamento de petabytes de dados. Fluxos de trabalho automatizados convertem imagens brutas em informações ambientais valiosas.

Essa abordagem abrangente de sensoriamento remoto proporciona benefícios significativos, incluindo melhorias na produtividade agrícola, redução no uso de fertilizantes por meio de aplicações de precisão, maior capacidade de resposta rápida a desastres e estratégias de conservação bem fundamentadas. Isso representa uma grande mudança em direção à gestão ambiental automatizada que sustenta a pesquisa climática, a conformidade regulatória e os objetivos de desenvolvimento sustentável por meio da análise de dados de observação da Terra.

Como o CAS usa visão computacional

Na CAS, aproveitamos o poder da tecnologia avançada de visão computacional para identificar, analisar e interconectar meticulosamente informações vitais extraídas de nossas fontes de dados. A Coleção de Conteúdo do CAS TM é o maior repositório de informações científicas curado por humanos, e grande parte do que selecionamos vai além do texto — estruturas moleculares relatadas presentes em diversas fontes documentadas, como publicações científicas, ELNs, registros internos do CAS e mais. Nossa abordagem à visão computacional nos permite descobrir padrões e relacionamentos intrincados dentro desses extensos conjuntos de dados, transformando informações brutas em insights significativos que impulsionam inovação e descoberta.

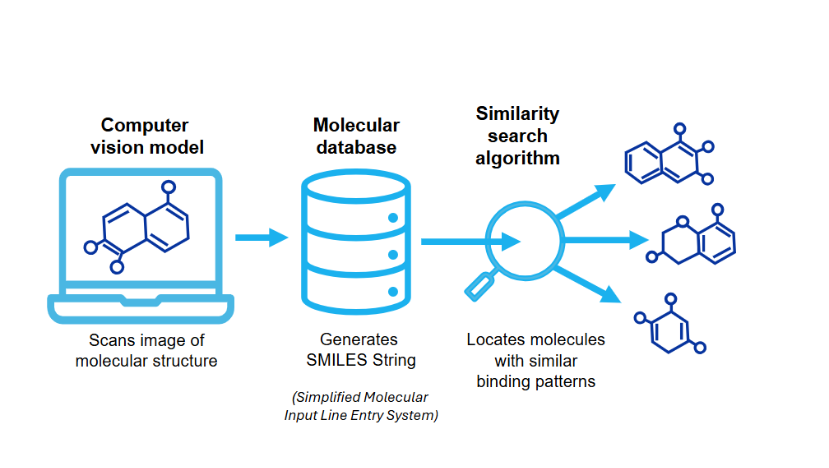

Nossos modelos de visão computacional identificam e categorizam estruturas moleculares, aprimoram algoritmos de busca e extraem dados valiosos de conteúdo científico complexo (ver Figura 1). Além disso, interpretam e analisam habilmente os resultados experimentais que são resumidos em tabelas detalhadas, fornecendo insights abrangentes sobre os achados científicos subjacentes. Incorporamos essas funcionalidades para enriquecer a coleção de conteúdo CAS e apoiar o Analytics.

Ao conectar pontos de dados extraídos a conteúdo estruturado e ontologias, simplificamos o acesso a informações cruciais e capacitamos cientistas a tomar decisões mais rápidas e mais bem informadas.

Etapas essenciais para desenvolver um plano de visão computacional

Para desenvolver um modelo robusto de visão computacional:

- Defina claramente o problema e reúna um conjunto de dados diversificado e bem anotado.

- Pré-processe seus dados redimensionando, normalizando e ampliando o que você tem. Isso deve ocorrer antes de dividir os dados em conjuntos de treinamento, validação e teste.

- Avalie sua pilha tecnológica nesta fase inicial. Seu hardware precisará de GPUs capazes de acelerar o treinamento e a inferência de modelos de aprendizado profundo.

- Aborde continuamente as questões éticas, garantindo que seu modelo esteja em conformidade com os regulamentos relativos a preconceito e privacidade.

- Escolha a arquitetura de modelo correta para treinamento e, em seguida, avalie seu desempenho usando métricas apropriadas no conjunto de dados de teste, fazendo melhorias iterativas conforme necessário.

- Implemente o modelo em um mundo real, monitorando seu desempenho e planejando uma possível reciclagem devido ao desvio de dados à medida que setores, domínios específicos e objetivos de negócios mudam com o tempo.

- Concentre-se na escalabilidade, otimização e documentação da arquitetura e dos processos do modelo para referência futura e compartilhamento de Conhecimento dentro da sua equipe.

A chave para o sucesso é envolver especialistas humanos no assunto em todas as etapas. É necessário conhecimento interdisciplinar para ajudar a entender as nuances do domínio, identificar dados relevantes, conduzir a anotação de dados, validar a qualidade dos dados e interpretar as saídas do modelo.

Assim como todas as tecnologias baseadas em IA, a visão computacional continuará a evoluir, e os modelos que aproveitam suas capacidades serão aprimorados ao longo do tempo. A importância dessa tecnologia para todas as áreas de investigação científica só continuará a crescer e, com descobertas importantes mais rápidas em campos que vão de descoberta de fármacos a ciência ambiental, poderemos enfrentar com mais eficácia os desafios que nosso mundo enfrenta.