La inmunoterapia es una de las rutas más prometedoras de la medicina en el tratamiento del cáncer, ya que transforma ingeniosamente el propio sistema inmunitario de los pacientes en arsenales personalizados para combatir el cáncer. Al eliminar las células malignas y preservar al mismo tiempo los tejidos sanos, este tipo de tratamiento consigue potencia y precisión, los dos pilares del éxito en el tratamiento del cáncer.

Mientras que la ola inicial de inmunoterapias ya ha revolucionado la oncología, una notable innovación está surgiendo ahora: los Bi-specific T cell engagers (Bi-TCEs). Estas proteínas modificadas representan quizás la solución más elegante hasta la fecha: puentes moleculares que obligan físicamente a las células cancerosas y las células inmunitarias a unirse, creando un encuentro mortal inevitable del que las células cancerosas no pueden escapar.

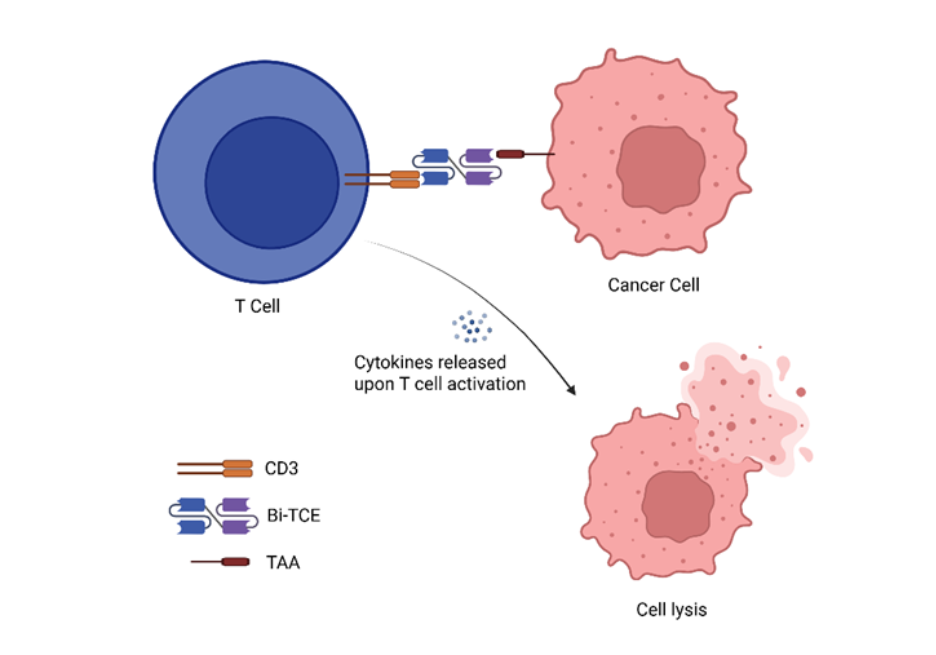

Estructuralmente, los Bi-TCE consisten en dos fragmentos variables de cadena única (scFv) conectados mediante un enlace flexible. Un scFv se une a un antígeno asociado al tumor (TAA), mientras que el otro se dirige al CD3, un componente clave del complejo receptor de células T. Esta doble especificidad permite a los Bi-TCE vincular físicamente cualquier célula T que exprese CD3 con las células cancerosas, lo que evita la necesidad de reconocer el péptido-MHC. Al activarse, los Bi-TCE desencadenan una potente cascada inmunológica que activa las células T, promoviendo su proliferación e induciendo la liberación de perforina y granzimas que median la lisis de células tumorales (véase Figura 1). Este mecanismo de acción ha demostrado ser eficaz en malignidades hematológicas, posicionando a los Bi-TCE como una ruta prometedora en inmunoterapia contra el cáncer.

Los engajadores biespecíficos de células T en el panorama de la inmunoterapia contra el cáncer

¿Cómo se comparan los Bi-TCE con el método predominante de inmunoterapia contra el cáncer, el CAR-T? Una diferencia clave es su método de producción: las terapias CAR-T se desarrollan mediante la ingeniería genética de las propias células T del paciente, mientras que los Bi-TCE se producen mediante la ingeniería de proteínas en anticuerpos de líneas celulares de mamíferos. Esto hace que los Bi-TCE sean un tipo de fármaco «listo para usar» y más sencillo de producir que las terapias CAR-T individualizadas.

Hay otras comparaciones importantes, que se resumen a continuación en la Tabla 1:

| Características | Células CAR-T | Bi-TCEs |

|---|---|---|

| Estructura | Lagradcitos T de pacientes modificados con un receptor sintético, incluyendo un dominio de unión al antígeno objetivo (scFv), una región bisagra, un dominio transmembrana y un dominio de señalización intracelular | Un anticuerpo recombinante con dos regiones de scFv conectadas; uno dirigido a un TAA y otro al CD3, parte del complejo TCR en células T. |

| Reclutamiento de células T | Células T activas y redirigidas para eliminar células tumorales | Pasivo, depende de las células T endógenas y las redirige para matar las células tumorales. |

| Mecanismo de la citotoxicidad | Liberación de perforina y granzima B de las células CAR T | Liberación de perforina y granzima B a partir de células T endógenas activadas por el Bi-TCE. |

| Tratamiento de linfodepleción antes de la terapia | Necesario (medicamentos como la fludarabina y la ciclofosfamida) | No se necesita |

| Semivida | Larga (de semanas a meses) | Corto (horas) – requiere infusiones repetidas |

| Producción | Ingeniería genética de las células T del paciente in vitro | Ingeniería proteica de anticuerpos procedentes de líneas celulares de mamíferos. |

| Disponibilidad | Proceso de producción individual para cada paciente | Fármacos «listos para usar» con procesos de producción relativamente sencillos. |

| Indicaciones | Principalmente malignidades hematológicas, desarrollo clínico temprano en fase de tumores sólidos | Principalmente malignidades hematológicas, los primeros resultados de tumores sólidos sugieren que, en comparación con CAR-T, los Bi-TCEs pueden tener ligeras ventajas en tumores sólidos. |

Las tendencias de publicación muestran cada vez más oportunidades en la investigación del cáncer y de otras condiciones

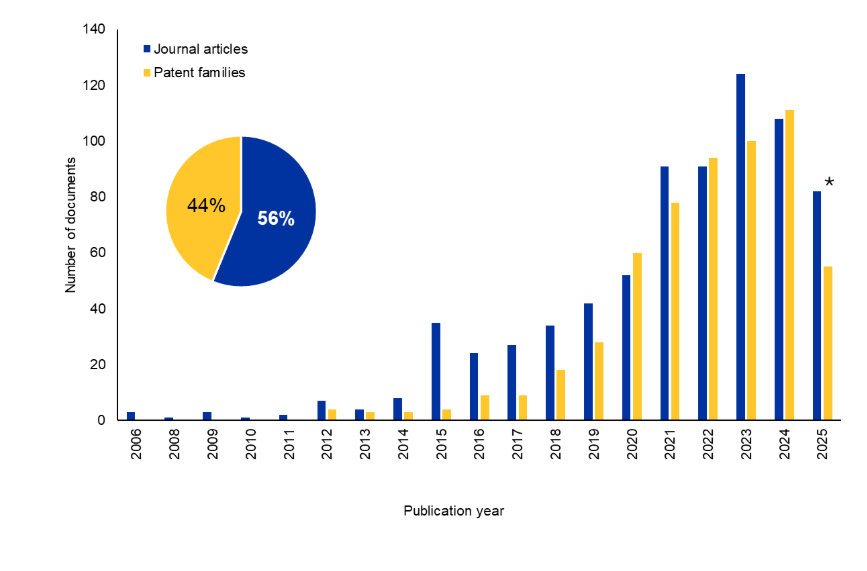

Examinamos la CAS Content CollectionTM, el mayor repositorio de información científica seleccionado por humanos, para comprender mejor el panorama de la investigación sobre Bi-TCE. Ha habido un aumento significativo en el número de documentos de revistas y patentes en los últimos 10 años. Curiosamente, las patentes poseen un 44 % del total de documentos, lo que indica un interés comercial sostenido en esta área (véase la Figura 2).

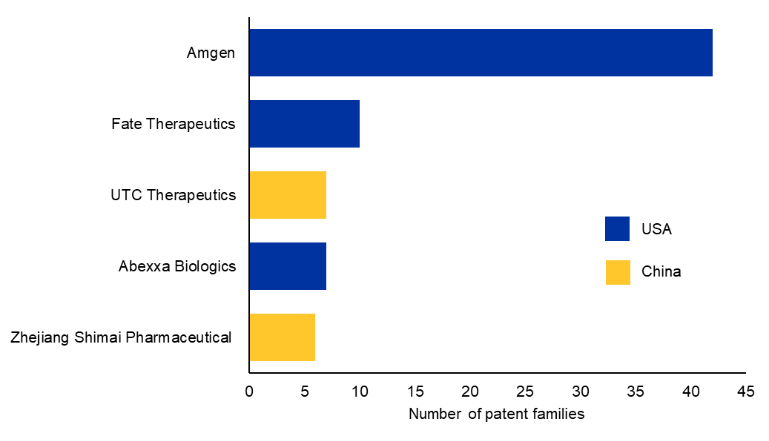

Analizamos los datos para encontrar los 10 principales cesionarios comerciales de patentes (véase la Figura 3). Amgen fue la primera en desarrollar una molécula Bi-TCE aprobada en todo el mundo para hematología, y sigue siendo líder en este campo con su tecnología patentada BiTE®.

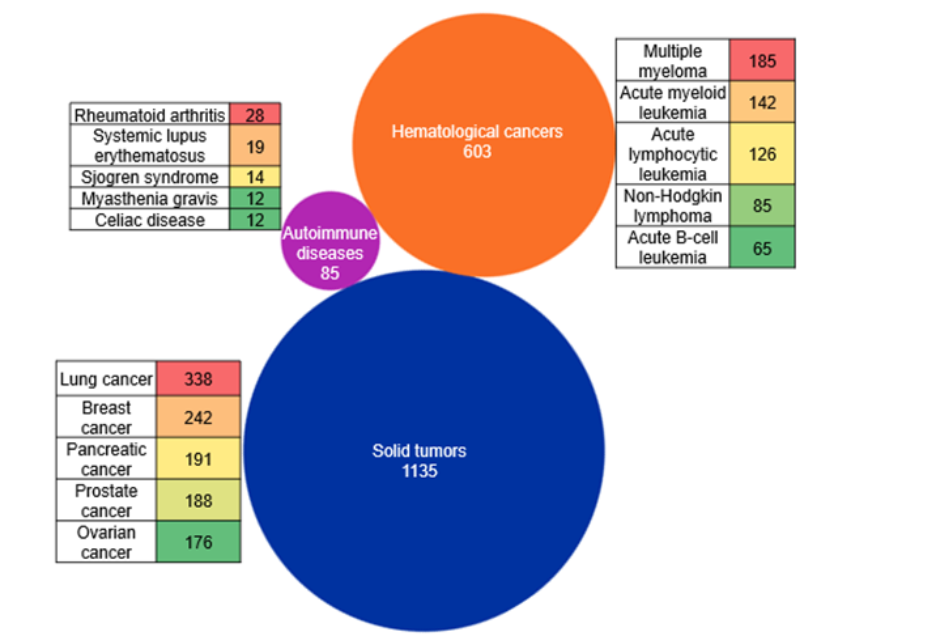

También exploramos las principales áreas terapéuticas en el contexto de Bi-TCE utilizando los conceptos indexados de CAS a los que se accede a través de CAS STNext®. Nuestro análisis del panorama muestra que el desarrollo de Bi-TCE se concentra predominantemente en tumores sólidos, con la mayor documentación sobre cánceres de pulmón, mama, páncreas, próstata y ovario. Las neoplasias hematológicas constituyen la segunda gran área de interés, impulsada en gran medida por los programas relacionados con el mieloma múltiple y las leucemias agudas (véase la figura 4).

En cambio, las enfermedades autoinmunes representan una nueva área más pequeña de exploración, con un interés distribuido en condiciones como la artritis reumatoide, el lupus eritemato sistémico y el síndrome de Sjörgen. Cabe destacar que la mayoría de los Bi-TCE aprobados por la FDA hasta ahora son para indicaciones hematológicas. Sin embargo, en nuestro análisis vemos que el número de documentos es mayor para tumores sólidos. Esto probablemente se deba al aumento continuo de las iniciativas para utilizar eficazmente los Bi-TCEs como indicaciones sólidas de tumores.

El primer Bi-TCE aprobado por la FDA, el blinatumomab, se autorizó en 2014. Se dirige a CD19 y CD3 y está indicado para la leucemia linfoblástica aguda de células B recidivante o refractaria. Desde entonces, muchos más tratamientos para los Bi-TCE han obtenido la aprobación agilizada de la FDA para diversos tipos de cáncer, incluidas dos indicaciones sólidas de tumores. Los detalles se resumen en la siguiente tabla 2:

| Nombre de Bi-TCE | Año de aprobación | Indicación terapéutica | Diana en las células tumorales |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blinatumomab (Blincyto) | 2014 | Leucemia linfoblástica aguda | CD19 en células B |

| Mosunetuzumab (Lunsumio) | 2022 | Linfoma folicular R/R | CD20 en células B |

| Tebentafusp (Kimmtrak) | 2022 | Melanoma uveal irresecable o metastásico | Péptido gp100-HLA-A en células de melanoma uveal |

| Teclistamab (Tecvayli) | 2022 | R/R mieloma múltiple | BCMA en células de mieloma |

| Elranatamab (Elrexfio) | 2023 | R/R mieloma múltiple | BCMA en células de mieloma |

| Epcoritamab (Epkinly) | 2023 | Linfoma difuso de células B grandes R/R | CD20 en células B |

| Glofitamab (Columvi) | 2023 | Linfoma difuso de células B grandes R/R, no especificado de otro modo; linfoma de células B grandes | CD20 en células B |

| Talquetamab (Talvey) | 2023 | R/R mieloma múltiple | GPRC5D en células de mieloma |

| Tarlatamab (Imdelltra) | 2024 | Cáncer de pulmón microcítico (SCLC) | DLL3 en las células SCLC |

Tabla 2:Resumen de los Bi-TCE aprobados por la FDA (incluyendo aprobaciones agilizadas, a noviembre de 2025). CD: clúster de diferenciación; GP100, glicoproteína 100; HLA-A, antígeno leucocitario humano-A; BCMA: antígeno de maduración de células B; GPRC5D: miembro D del grupo 5 de receptores acoplados a proteínas G; DLL3: Ligando tipo Delta 3, R/R: Recaída o refractario. Fuente: Administración de Alimentos y Medicamentos de EE. UU.

Las limitaciones de los Bi-TCE como cura del cáncer

Los Bi-TCE se consideran transformadores en los cánceres hematológicos, pero aún presentan varias limitaciones. Los Bi-TCE clásicos (por ejemplo, los BiTE como el blinatumomab) son pequeños fragmentos de anticuerpos (~55 kDa) que carecen de dominio Fc. Esto significa que se eliminan rápidamente por filtración renal, lo que da como resultado una vida media plasmática de solo unas pocas horas. Se requiere una infusión intravenosa continua para mantener las concentraciones terapéuticas, lo que aumenta la carga sobre los pacientes y los recursos sanitarios.

Los Bi-TCE provocan la activación policlonal de las células T mediante la reticulación del CD3 con antígenos tumorales, lo que provoca una secreción masiva de citocinas (IL 6, IFN γ, TNF α) conocida como síndrome de liberación de citocinas (CRS). El CRS se manifiesta con fiebre, hipotensión y disfunción multiorgánica. Los Bi-TCE también están asociados con un riesgo de neurotoxicidad, específicamente un síndrome de neurotoxicidad asociado a células efectoras inmunes (ICANS). Estas toxicidades pueden ser potencialmente mortales y requieren hospitalización, corticosteroides o bloqueo del receptor IL 6 (por ejemplo, tocilizumab).

Los Bi-TCE presentan una fuerte actividad en malignidades hematológicas, pero han mostrado una utilidad clínica limitada en los tumores sólidos. Las barreras incluyen la penetración del tumor, la heterogeneidad de los antígenos y el microambiente inmunosupresor. Otra limitación crítica de los Bi-TCE es el fenómeno de toxicidad en el objetivo, fuera del tumor. Muchos antígenos asociados a los tumores (por ejemplo, CD19, BCMA, EpCAM) también se expresan en niveles bajos en los tejidos normales. En consecuencia, los Bi-TCE pueden redirigir las células T para atacar células sanas, provocando daños colaterales en el tejido y limitando la selección de antígenos.

Desarrollos recientes en la investigación del cáncer con Bi-TCEs

Los recientes avances en los Bi-TCE reflejan una iniciativa organizada para abordar los desafíos mencionados y conducir un mayor impacto clínico con estos tratamientos. Las innovaciones continuas están mejorando su precisión, seguridad y durabilidad, posicionando a los BiTCE como una clase de inmunoterapias en rápida evolución con un potencial en expansión a través de diversos tipos de cáncer. Algunos de los métodos destacados son:

Bi-TCE de vida media extendida (HLE Bi-TCE):

Las moléculas canónicas de Bi-TCE tienen una vida media corta de dos a cuatro horas debido a la ausencia de un dominio Fc, lo que requiere una infusión intravenosa continua. Para solucionarlo, se están desarrollando Bi-TCE HLE que fusionan el Bi-TCE con un dominio Fc, lo que permite el reciclaje de FcRn y una circulación prolongada. Los estudios preclínicos y clínicos iniciales muestran que los Bi-TCE HLE mantienen su actividad con CD19 y BCMA HLE Bi-TCE alcanzando vidas medias de hasta 210 horas, apoyando la dosificación semanal.

Ajuste de CD3 y formatos 2:1:

La afinación de CD3 en los Bi-TCE implica ajustar la afinidad del brazo de unión a CD3 para controlar la activación de las células T. La unión a CD3 de menor afinidad reduce la liberación excesiva de citoquinas y sigue permitiendo la destrucción eficaz de células tumorales, mejorando así la seguridad. El formato 2:1 coloca dos dominios de unión para el antígeno tumoral y uno para el CD3, lo que aumenta la selectividad y la potencia del tumor al garantizar una mayor interacción con las células cancerosas antes de activar las células T. En conjunto, el ajuste de CD3 y el formato 2:1 son estrategias clave de ingeniería para equilibrar eficacia y tolerabilidad en terapias Bi-TCE de próxima generación.

Agentes de doble objetivo y triespecíficos:

Para dar respuesta a la heterogeneidad y el escape de antígenos, los investigadores están promoviendo agentes de doble objetivo y triespecíficos que se dirigen a dos antígenos tumorales para aumentar la especificidad y la cobertura, o añadir un componente coestimulador para mejorar la aptitud de las células T en entornos inmunosupresores. Los activadores de las células T de doble especificidad tienen dos sitios de unión: uno para el CD3 de las células T y otro para el antígeno asociado a un tumor, lo que provoca la formación de sinapsis inmunitarias y la citotoxicidad. Los agentes triespecíficos (TriTE) amplían este diseño con un tercer sitio de unión, que puede dirigirse a un segundo antígeno tumoral para evitar la fuga o activar un receptor coestimulador como CD28 para potenciar la activación de las células T. Este dominio adicional aumenta la selectividad y la potencia, asegurando un reconocimiento tumoral más fuerte antes del acoplamiento de las células T. Los métodos «AND-gate» que aprovechan la doble focalización del antígeno tumoral son útiles para reducir la toxicidad dentro y fuera del objetivo de los Bi-TCE.

Nuevos sistemas de administración:

Los nuevos sistemas de administración para los Bi-TCE intentan superar las limitaciones de la vida media corta y la infusión continua. La terapia génica basada en AAV permite la expresión in vivo de los Bi-TCE, lo que permite una producción sostenida a partir de las propias células del paciente y potencialmente permite el tratamiento de dosis única. Además, se están explorando otros métodos, como las vesículas extracelulares para administrar Bi-TCE directamente en el microambiente tumoral y así mejorar la activación inmune local.

Otras estrategias incluyen atacar los nuevos antígenos tumorales para ampliar su eficacia en los tumores sólidos. Algunos Bi-TCE utilizan activación mediada por el microambiente, uniéndose solo bajo condiciones específicas del tumor para reducir la toxicidad fuera del objetivo. Se están añadiendo dominios de unión a la albúmina a los Bi-TCE para prolongar la vida media y mejorar la farmacocinética aprovechando el reciclaje natural de albúmina. Los Bi-TCE también se están combinando con inhibidores de puntos de control, citocinas o terapias celulares para potenciar la activación inmunitaria y superar los mecanismos de resistencia.

Los ensayos clínicos sugieren direcciones futuras para las terapias con Bi-TCE

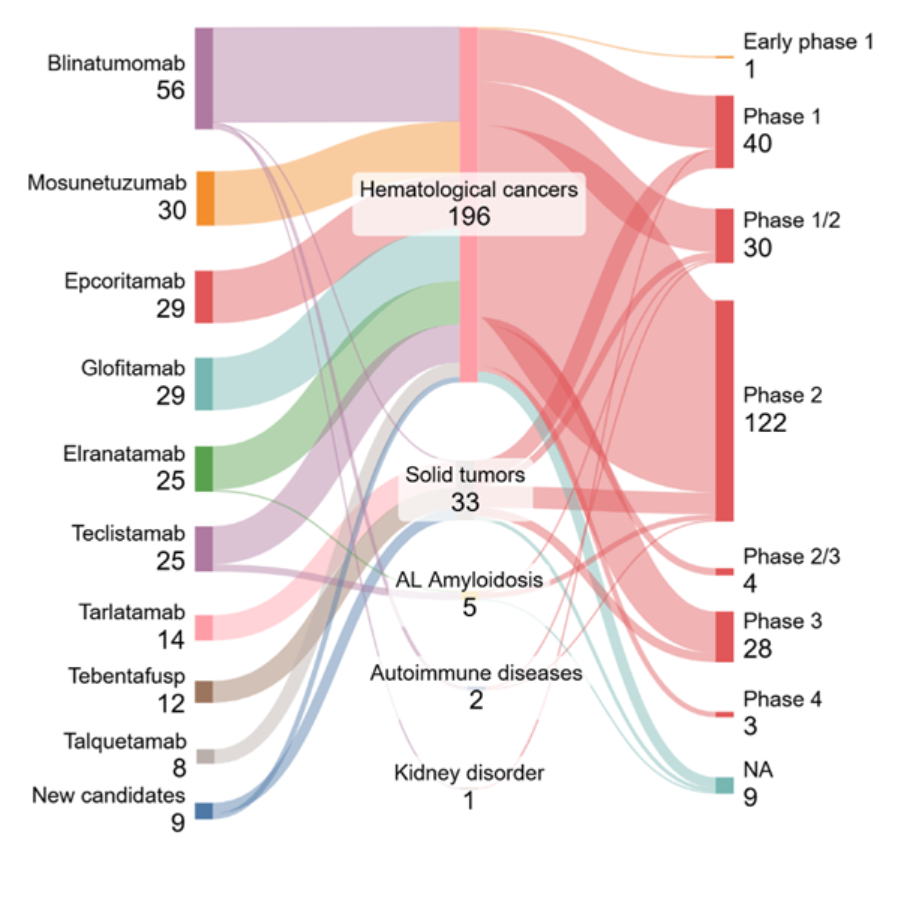

Analizamos los datos de Clinicaltrials.gov para obtener información sobre el panorama actual de los ensayos clínicos en este campo. Como se ve en la Figura 5, la mayoría de los ensayos con estado «Activo, seleccionando» se relacionan con candidatos bien establecidos y aprobados por la FDA, que lideran el dominio del cáncer hematológico (196 ensayos). Una proporción menor pero significativa se relaciona con los tumores sólidos (33 ensayos) con iniciativas limitadas en las enfermedades autoinmunes, amiloidis de cadena ligera (amiloidosis AL) y los trastornos renales.

En todas las indicaciones, la mayor concentración de ensayos se encuentra en la fase 2 (122), seguida de la fase 1 (40) y la fase 1/2 (30), lo que indica un pipeline clínico que está madurando pero que aún se centra en actividades de fase temprana a media. Solo unos pocos candidatos han alcanzado la fase 3 (28 ensayos), lo que refleja los problemas de sacar las terapias de redirección de células T de los entornos hematológicos.

Nuestro análisis destaca dos tendencias principales: un fuerte impulso clínico en las malignidades de células B y una expansión gradual de los Bi-TCEs en tumores sólidos y enfermedades no oncológicas. Algunos de los ensayos clínicos de fase 3 para tumores sólidos implican fármacos aprobados en combinación con otros quimioterapias o inhibidores de puntos de control inmunitarios (por ejemplo, Tebentafusp + Pembrolizumab).

Los nuevos fármacos candidatos, que la FDA aún no ha aprobado, y sus detalles se resumen en la Tabla 3:

| Bi-TCE candidato (Empresa) | Indicación | Diana en las células tumorales | ID del ensayo clínico, fase | Aspectos destacados de la innovación |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AZD0486 (AstraZeneca) | Malignidades de células B | CD19 | NCT06564038, Fase 1/2 | CD3 de baja afinidad para CRS reducido |

| XmAb541 (Xencor, Inc.) | Cáncer de ovario, cáncer de endometrio, tumor de células germinativas | CLDN6 | NCT06276491, Fase 1 | Formato 2+1 para selectividad |

| BI764532 (Boehringer Ingelheim) | Cáncer de pulmón microcítico, tumores neuroendocrinos | DLL3 | NCT05882058, Fase 2 | Bi-TCE de tumores sólidos con diana DLL3 |

| BA3182 (BioAtla, Inc.) | Adenocarcinoma avanzado | EpCAM | NCT05808634, Fase 1 | Unión condicionalmente activa, solo en el microambiente tumoral |

| CLN-049 (Cullinan Therapeutics Inc.) | R/R AML, MDS | FLT3 | NCT05143996, Fase 1 | Nuevo antígeno tumoral (FLT3) |

| AMG 509 (Amgen) | Cáncer de próstata | STEAP1 | NCT04221542, Fase 1 | Formato 2+1, novedoso antígeno tumoral sólido (STEAP1) |

| AMF 305 (Amgen) | Tumores sólidos avanzados | CDH3/MSLN | NCT05800964, Fase 1 | Bi-TCE de doble objetivo |

| VNX-202 (Vironexis Biotherapeutics Inc.) | Tumores sólidos que expresan HER2 | HER2 | NCT07192432, Fase 1/2 | Terapia génica AAV para la administración in vivo de Bi-TCE |

| VNX-101 (Vironexis Biotherapeutics Inc.) | Malignidades de células B | CD19 | NCT06533579, Fase 1/2 | Terapia génica AAV para la administración in vivo de Bi-TCE |

Tabla 3: Resumen de los candidatos destacados a Bi-TCE en el desarrollo clínico. Abreviaturas: R/R: Recaída/Refractaria; AML: Leucemia mieloide aguda; MDS: Síndrome Mielodisplásico; EpCAM: molécula de adhesión de células epiteliales; CLDN6: Claudin-6; FLT3: FMS como tirosina quinasa 3; STEAP1: Antígeno epitelial transmembrana de la próstata 1; CDH3: cadherina-3; MSLN: mesotelina; HER2: receptor 2 del factor de crecimiento epidérmico humano; AAV: Virus adeno-asociado.

Estos nuevos Bi-TCE han demostrado un potencial considerable y resultados favorables en estudios clínicos iniciales. Demuestran que el campo está evolucionando rápidamente, y el desarrollo de Bi-TCE de próxima generación tiene como objetivo mejorar la eficacia y mejorar los perfiles de seguridad.

Los Bi-TCE están haciéndose con un nicho crucial en el tratamiento oncológico y están preparados para ofrecer mejores resultados a los pacientes. También pueden desempeñar un papel importante en el tratamiento de enfermedades distintas del cáncer. A medida que se amplíe la investigación, pronto podrían ofrecer más avances y esperanza para los pacientes de todo el mundo.

Tabla 1, referencias:

Slaney CY, Wang P, Darcy PK, Kershaw MH. CARs versus BiTEs: A Comparison between T Cell-Redirection Strategies for Cancer Treatment. Cancer Discov. Agosto de 2018; 8(8): 924-934. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-0297. Epub 2018 Jul 16. PMID: 30012854.

Edeline, J., Houot, R., Marabelle, A. et al. Células CAR-T y BiTEs en tumores sólidos: desafíos y perspectivas. J Hematol Oncol 14, 65 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-021-01067-5

Dalal PJ, Patel NP, Feinstein MJ, Akhter N. Adverse Cardiac Effects of CAR T-Cell Therapy: Characteristics, Surveillance, Management, and Future Research Directions. Technology in Cancer Research & Treatment. 2022; 21. doi:10.1177/15330338221132927