공유결합 유기 골격체(Covalent Organic Frameworks, COF)는 최근 몇 년 사이 주목도가 크게 높아진 결정성 다공성 소재의 한 유형입니다. COF는 유기 빌딩 블록이 강한 공유결합으로 연결되어 형성된 구조로, 예측 가능한 토폴로지를 갖는 이차원(2D) 또는 삼차원(3D) 확장 네트워크를 이루며 뛰어난 구조 제어가 가능하다는 특징을 지닙니다.

최근에는 다른 유형의 다공성 소재 역시 주목을 받고 있는데, 그중 대표적인 예가 2025년 노벨 화학상의 주제가 된 금속-유기 골격체(MOF)입니다. MOF는 가스 분리, 촉매, 에너지 저장은 물론 센서와 같은 바이오의학적 응용 분야에서도 잠재력을 인정받고 있습니다. COF 역시 유사한 기능적 특성을 바탕으로 이러한 응용 분야에 활용될 수 있습니다. 그러나 MOF나 제올라이트와 같은 다른 다공성 소재와 달리, COF는 탄소, 수소, 질소, 산소, 붕소 등과 같은 경량 원소로만 구성되어 있다는 점에서 차별화됩니다.

이와 같은 무금속 조성은 COF 소재를 더 가볍게 만들고 가수분해에 대한 민감도를 낮추며, 뛰어난 화학적·열적 안정성을 부여합니다. 또한 MOF는 금속 노드를 포함해 독성이나 환경적 우려가 제기될 수 있는 반면, COF는 재활용 가능성과 낮은 독성 잠재력을 갖춘 보다 지속 가능한 대안으로 평가됩니다.

COF는 종종 2000m²/g를 초과하는 매우 높은 비표면적과 함께, 미세공부터 중간공까지 조절 가능한 기공 크기를 나타냅니다. 이러한 특성에 더해 영구적인 다공성, 낮은 밀도, 용이한 표면 기능화, 그리고 합성 전·후 개질이 가능하다는 점은 COF의 주요 장점으로 꼽힙니다.

결정성 기공 구조, 조절 가능한 아키텍처, 높은 구조적 정밀성의 독특한 조합은 COF를 가스 저장 및 분리, 촉매, 센싱, 광전자 등 다양한 응용 분야의 핵심 소재로 자리매김하게 했습니다. 이 분야의 연구가 지속적으로 확대됨에 따라, COF는 탄소 포집, 청정 에너지 저장, 고도화된 약물 전달 시스템, 환경 정화에 이르는 차세대 기술 전반에서 더욱 중요한 역할을 수행할 것으로 기대됩니다.

출판 데이터 역시 COF에 대한 관심 증가를 뒷받침합니다. 인간이 엄선한 세계 최대 규모의 과학 정보 저장소인 CAS Content Collection™을 분석한 결과, COF는 2005년 Yaghi 연구진에 의해 처음 보고된 이후 기하급수적인 성장세를 보여 왔음을 확인했습니다(그림 1 참조).

초기 약 10년간의 출판 활동은 비교적 제한적이었으며, 이는 해당 분야가 탐색 단계에 있었음을 반영합니다. 그러나 2016년 전후로 학술 논문과 특허 패밀리 수가 가파르고 지속적으로 증가하기 시작했으며, 이는 기초 연구 중심 단계에서 응용 지향적 연구로의 전환이 이루어졌음을 시사합니다. 이러한 성장은 COF에 대한 과학적 관심 확대와 함께 실제 기술 혁신과의 연관성이 커지고 있음을 보여줍니다.

COF 구조의 작동 원리

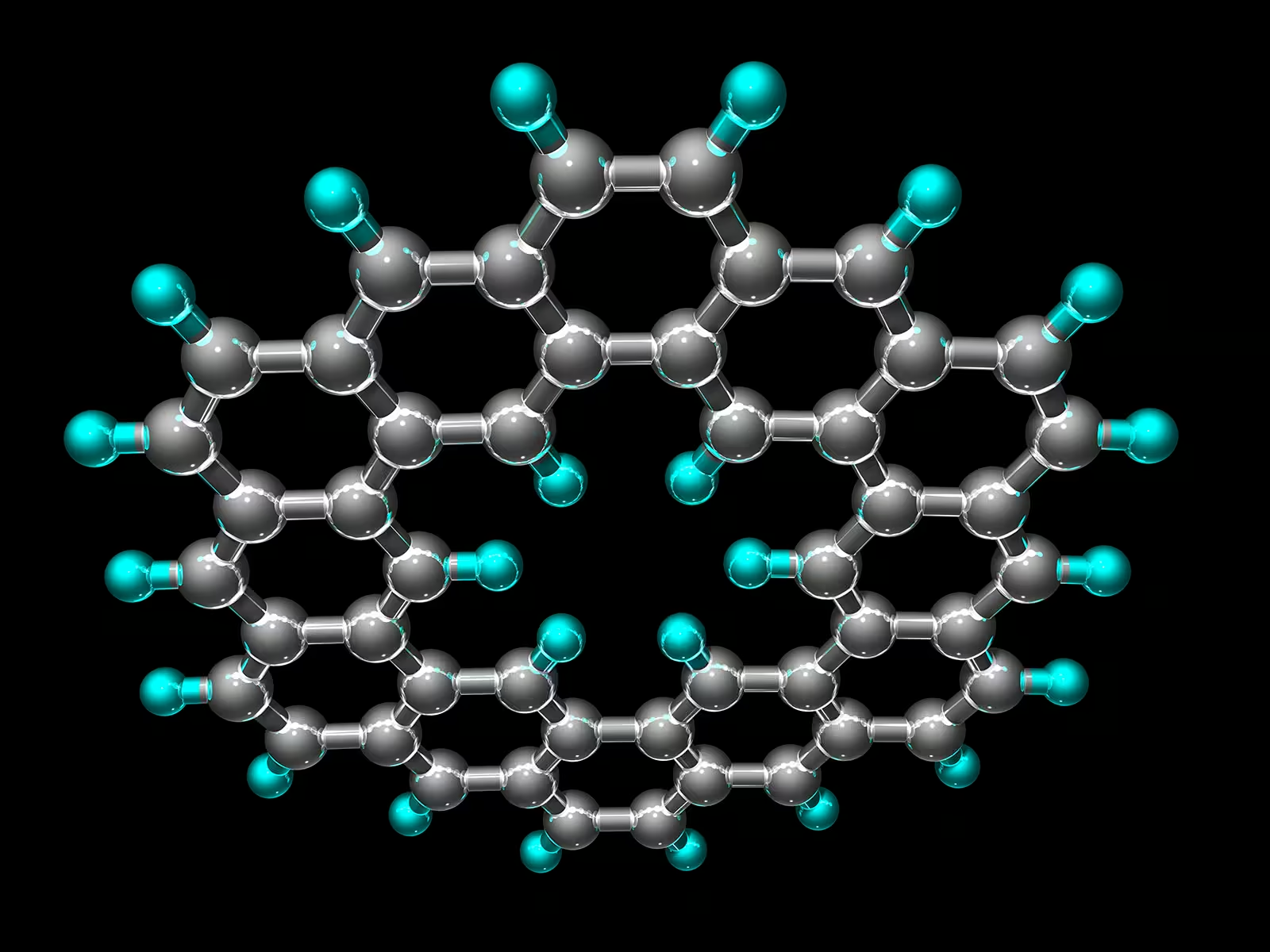

COF의 뛰어난 범용성은 모듈식 합성에 기반합니다. 이는 엄선된 유기 단량체를 체계적으로 연결해 확장된 결정성 네트워크를 형성하는 방식입니다. 이러한 단량체는 용매열 또는 기계화학 조건에서 결합되며, 이 과정에서 이민(C=N), β-케토에나민, 보로네이트 에스터, 하이드라존, 아진, 트리아진과 같은 특정 결합이 형성됩니다.

단량체의 선택, 즉 기하구조, 기능기, 결합 유형은 COF가 2차원(2D) 적층 구조를 취할지, 또는 3차원(3D) 골격 구조를 형성할지를 직접적으로 결정합니다. 2D COF에서는 평면 시트가 π–π 상호작용을 통해 적층되는 반면, 3D COF에서는 사면체형 또는 C₃ 대칭의 빌딩 블록이 서로 연결된 다면체 네트워크를 형성합니다. 또한 2D COF는 면내 전도성이 높은 반면, 3D COF는 더 큰 비표면적과 상호 연결된 기공 네트워크를 제공합니다.

CAS Content Collection에 수록된 데이터를 바탕으로 CAS SciFinder®와 CAS STNext® 등의 도구를 활용해 COF 구조에 가장 널리 사용되는 단량체를 분석했습니다(그림 2a 참조). 그 결과, 1,3,5-트리포밀플로로글루시놀(Tp), 1,3,5-벤젠트리카복살데하이드(TFB), 2,5-디메톡시-1,4-벤젠디카복살데하이드(DMTA)와 같은 알데하이드류와, p-페닐렌디아민(Pa-1 또는 PDA), 1,3,5-트리스(4-아미노페닐)벤젠(TAPB), 4,4′,4′′-(1,3,5-트리아진-2,4,6-트릴)트리스벤젠아민과 같은 아민류가 주요 단량체로 확인되었습니다. 이들 단량체는 각각 상이한 반응성, 강한 공액성, 구조적 영향을 제공하며, 2D 및 3D 아키텍처 형성을 뒷받침합니다.

예를 들어, Tp는 방향족 아민과 반응해 화학적으로 매우 안정적인 β-케토에나민 결합을 형성하는 것으로 알려져 있으며, 이로 인해 산성 또는 고습 환경에서도 결정성을 유지하는 COF를 구현할 수 있습니다. 이러한 특성 덕분에 해당 구조는 촉매, 센싱, 에너지 저장 분야에 적합합니다.

또한 TAPB와 TAPT와 같은 보다 복잡한 C₃ 대칭 아민은 각각 확장된 π-시스템과 전자결핍 트리아진 코어를 도입해 결정성과 화학적 내구성을 향상시킵니다. 그림 2b에는 TpPa-1, TpTAPT, TAPB-DMTA 등 이러한 단량체로 구성된 대표적인 COF 구조가 제시되어 있으며, 이를 통해 토폴로지, 기공 형상, 차원성의 다양성을 확인할 수 있습니다. 이 사례들은 단량체 기하구조(예: 선형 vs. 삼각형)와 결합 유형의 차이가 다공성, 결정성, 화학적 안정성과 같은 물성에 직접적인 영향을 미친다는 점을 보여줍니다.

아울러 CAS 데이터베이스에서 가장 빈번하게 활용된 상위 10개 COF를 분석한 결과(그림 3 참조), TpPa-1이 가장 지배적인 골격 구조로 나타났으며, 그 뒤를 TAPB-DMTA와 TFB-PDA가 이었습니다. TpPa-1은 β-케토에나민 결합을 기반으로 한 2D 적층 구조를 형성하며, 이는 가혹한 화학적·열적 조건에서도 탁월한 안정성을 제공합니다.

반면 TAPB-DMTA와 TFB-PDA는 이민 결합을 포함하고 있어 높은 결정성, 우수한 가수분해 안정성, 명확한 기공 구조를 구현할 수 있으며, 정밀한 분자 배열이 요구되는 응용 분야에 특히 적합합니다. 주목할 점은 그림 3에 제시된 10개 COF 모두가 이민 결합 또는 β-케토에나민 결합을 포함하고 있다는 사실로, 이는 COF 설계에서 이들 결합이 널리 활용되고 있음을 보여줍니다. 이러한 결합은 합성 용이성, 구조적 유연성, 화학적 견고함이 결합된 독특한 특성 조합을 제공하며, 조절 가능한 물성을 갖춘 안정적인 결정성 골격을 형성할 수 있다는 점에서 다양한 COF 연구와 응용에서 선호되는 선택지로 활용되고 있습니다.

에너지, 환경 정화, 바이오기술 분야에서의 COF 응용

COF는 촉매, 바이오의학, 센싱, 에너지 및 가스 저장, 전자 분야를 포함한 다양한 과학·기술 영역에서의 활용 가능성으로 주목받고 있습니다(그림 4A 참조). 관련 출판물의 분포를 보면 촉매 분야가 가장 큰 비중을 차지하고 있으며, 그 뒤를 에너지 저장과 바이오의학 응용이 잇고 있습니다. 또한 COF는 비독성, 생체적합성, 그리고 특정 오염물에 맞게 조절 가능한 기공 크기를 바탕으로 환경 정화 분야에서도 폭넓게 활용되고 있습니다.

그림 4B는 이러한 응용 분야 전반에서 가장 유망한 COF 활용 사례를 보여줍니다. 예를 들어, 트리아진, 포르피린, 벤조티아디아졸과 같은 광활성 단위와 확장된 π-공액 구조를 갖는 COF는 가시광 흡수, 전하 분리 및 수송을 가능하게 합니다. 이로 인해 COF는 반도체 및 광전자 소자를 포함한 광촉매 및 전자 응용에 적합하며, 발광 다이오드(LED), 전계 효과 트랜지스터(FET), 광검출기와 같은 장치에도 활용될 수 있습니다.

에너지 저장 분야에서 COF는 주로 배터리 응용, 특히 전극 소재로 사용됩니다. 이는 리튬 이온(Li⁺)이나 나트륨 이온(Na⁺)과 같은 이온이 빠르게 확산할 수 있는 정렬된 다공성 채널과, 카보닐기, 이민기, 아조 단위 등과 같은 산화·환원 활성 부위를 통해 가역적인 전하 저장이 가능하기 때문입니다.

바이오의학 분야에서는 COF의 생체적합성과 모듈성은이 약물 전달 및 광역학 치료, 광열 치료, 병합 치료와 같은 치료 응용에 적합합니다. 또한 높은 비표면적, 정렬된 결정성 다공 구조, 조절 가능한 화학적 기능성 덕분에 수처리 및 담수화, 생체분자·가스·이온의 선택적 센싱, 그리고 CO₂, H₂, CH₄와 같은 가스의 효율적인 흡착 및 분리에도 활용됩니다.

문헌에서 가장 빈번하게 인용된 상위 10개 COF를 다시 살펴보면, 이들이 7개 주요 응용 분야 전반에 걸쳐 활용되고 있음을 확인할 수 있습니다(그림 5 참조). 이 분석에 따르면 거의 모든 COF가 촉매 분야에 사용되고 있는데, 이는 높은 비표면적, 용이한 기능화, 우수한 재활용성 덕분에 효율적이고 선택적인 촉매 공정을 구현하기에 적합하기 때문입니다.

또한 TpPa-1은 환경 정화 분야에서도 활용되는 반면, TAPB-DMTA는 바이오의학 및 센서 응용에서 널리 사용되고 있습니다. 아울러 TpPa-SO₃H는 에너지 저장 분야에서 두드러진 활용 사례를 보입니다. 이는 COF가 지닌 구조적·화학적 다양성이 다양한 첨단 기술 분야에 맞춰 맞춤형으로 활용될 수 있음을 보여줍니다.

COF의 향후 전망

유망한 물성을 지니고 있음에도 불구하고, COF는 아직 광범위한 활용과 상용화를 제한하는 몇 가지 핵심 과제에 직면해 있습니다. 주요 문제 중 하나는 합성 공정의 확장성과 재현성 부족입니다. 많은 COF는 용매열 처리, 긴 반응 시간, 또는 강한 용매와 같은 특정 조건을 요구해 대량 생산이 쉽지 않습니다. 또한 COF는 결정성이 중요한 장점으로 평가되지만, 높은 결정성과 구조적 균일성을 안정적으로 확보하는 것 자체가 여전히 큰 과제이며, 결정성이 낮을 경우 성능 저하로 이어질 수 있습니다.

다수의 COF가 지니는 제한적인 전기 전도성 역시 전자 소자나 에너지 장치에 별도의 개질 없이 직접 적용하는 데 제약으로 작용합니다. 여기에 더해, 박막이나 복합체 형태로 가공하기 어렵다는 점과, 고습·산성·산화 환경에서의 열화 가능성은 실제 장치에의 통합을 더욱 어렵게 만듭니다.

이러한 과제를 해결하기 위해 연구자들은 여러 전략적 접근을 시도하고 있습니다. 기존의 용매열 공정을 대체하기 위해 기계화학적 합성, 마이크로파 보조 반응, 상온 반응과 같은 확장 가능하고 친환경적인 합성 방법이 개발되고 있으며, 이를 통해 생산 효율과 환경 적합성을 개선하고자 하고 있습니다.

또한 토폴로지 예측 기술과 AI 기반 설계의 발전은 새로운 COF 구조의 발굴 속도를 크게 높이고 있습니다. MOF, 고분자, 심지어 나노소재 등을 결합한 하이브리드 COF 개발 역시 활발히 진행되고 있으며, 이를 통해 COF와 기존 소재의 장점을 결합한 다기능적 특성이 구현되고 있습니다. 이러한 발전은 COF가 복잡한 합성의 한계를 넘어 특정 응용을 염두에 둔 소재 설계 단계로 이동하고 있음을 보여줍니다.

모듈성, 결정성, 그리고 조절 가능한 물성을 갖춘 COF는 에너지 및 가스 저장부터 바이오의학에 이르기까지 폭넓은 분야에서 활용 가능성을 지니고 있습니다. 합성 기법, 기능 설계, 계산 기반 스크리닝 기술이 지속적으로 발전함에 따라, COF는 유망한 실험실 소재를 넘어 지속 가능하고 고성능 기술을 구현하는 핵심 소재로 자리 잡을 수 있을 것으로 기대됩니다.

---

이 기사에서 사용된 약어는 다음과 같습니다: PBA, 페닐보론산; 4-FPBA, 4-포밀페닐보론산; Pa-1 또는 PDA, p-페닐렌디아민; TpPa-1, 1,3,5-트리포밀플로로글루시놀 및 p-페닐렌디아민; TAPB-DMTA, 1,3,5-트리스(4-아미노페닐)벤젠 및 2,5-디메톡시-1,4-벤젠디카복살데하이드; TFB-PDA, 1,3,5-벤젠트리카복살데하이드 및 p-페닐렌디아민; TAPB-TPA, 1,3,5-트리스(4-아미노페닐)벤젠 및 1,4-벤젠디카복살데하이드; TpBD, 1,3,5-트리포밀플로로글루시놀 및 4,4′-디아미노디페닐; TFB-TAPB, 1,3,5-벤젠트리카복살데하이드 및 1,3,5-트리스(4-아미노페닐)벤젠; TAPB-DHTA, 1,3,5-트리스(4-아미노페닐)벤젠 및 2,5-디하이드록시-1,4-벤젠디카복살데하이드; TpPa-SO3H, 1,3,5-트리포밀플로로글루시놀 및 2,5-디아미노벤젠설폰산; TpTAPT, 1,3,5-트리포밀플로로글루시놀 및 4,4′,4′′-(1,3,5-트리아진-2,4,6-트릴)트리스[벤젠아민]; TAPB-DVA, 1,3,5-트리스(4-아미노페닐)벤젠 및 2,5-디에테닐-1,4-벤젠디카복살데하이드; TFB, 1,3,5-벤젠트리카복살데하이드; Tp, 1,3,5-트리포밀플로로글루시놀; TAPB, 1,3,5-트리스(4-아미노페닐)벤젠; TpPa-1, 1,3,5-트리포밀플로로글루시놀 및 p-페닐렌디아민; TAPB-DMTA, 1,3,5-트리스(4-아미노페닐)벤젠 및 2,5-디메톡시-1,4-벤젠디카복살데하이드; TpTAPT, 1,3,5-트리포밀플로로글루시놀 및 4,4′,4′′-(1,3,5-트리아진-2,4,6-트릴)트리스[벤젠아민]; TAPT, 4,4′,4′′-(1,3,5-트리아진-2,4,6-트릴)트리스[벤젠아민]; BDBA, 벤젠-1,4-디보론산; DHTA, 2,5-디하이드록시-1,4-벤젠디카복살데하이드; DMTA, 2,5-디메톡시-1,4-벤젠디카복살데하이드; DVA, 2,5-디에테닐-1,4-벤젠디카복살데하이드; TPA, 1,4-벤젠디카복살데하이드; Pa-SO3H, 2,5-디아미노벤젠설폰산; BD, 4,4′-디아미노디페닐.